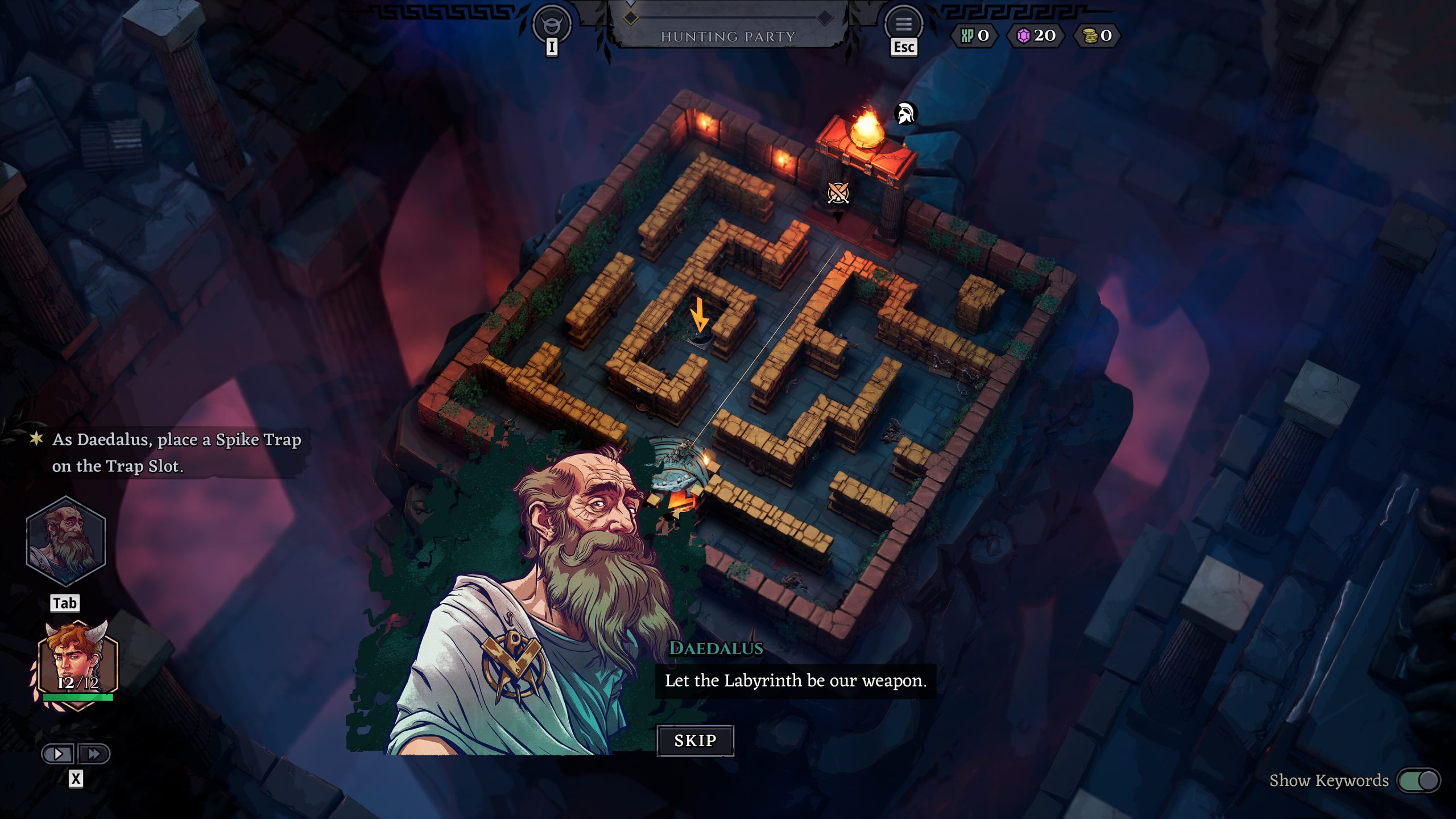

You can always trust Devolver Digital to back interesting, quirky and different projects. One recent example of this is Minos, which is a dungeon-building roguelike from one of its own studios, Artificer.

As a fan of Dungeons and Dungeon Keeper, my interest in this was immediately piqued, so we sat down with Kacper Szymczak, the CEO/Creative Director at Artificer to dig deep (see what I did there) into what they’re trying to achieve with this game.

I’m now even more excited for it. It certainly seems like they’re put a lot of thought into this one.

Minos reimagines the myth of the minotaur from the monster’s perspective. What drew you to retelling this story, and how did you decide to merge it with a roguelike/strategy framework?

Kacper Szymczak: It started off with the maze.

Most of the games I’m excited about making bring something new, something exciting to design. So when a couple of years ago the idea to make a maze-designing game popped into my head, I had a feeling I’m onto something. Making the player feel like they’re designing mazes sounded like a fascinating design problem.

Note that having the player design mazes and having them experience designing a maze are vastly different things; it’s all about striking the right balance between believability of the interaction, effectiveness and significance of said interaction, and agency that creates enough room for a feeling of expertise.

The second part is that I’m always looking for strong themes, deeply embedded in culture, widely recognized, understood and valued.

Thus, the Minotaur myth was an instant perfect fit, without significant telling of the story in our medium. Or any medium for that matter, it seems? Apart from the short novel “The House of Asterion”, we didn’t run into any famous work of fiction with the Minotaur as the protagonist.

Lastly, the roguelike structure is the perfect fit for a highly systemic game (as opposed to one based on content). Since we set out to make a game that makes it interesting to design a maze, by extension it should work on plenty of mazes, ensuring interchangeable elements that keep things fresh and interesting. At the same time, a roguelite does not alienate players whose skills are not a great match with the game’s difficulty.

We put these three elements together, and the project was entrusted with a budget by the folks at Devolver, as we set off to prototype it late last summer.

Dungeon Keeper and the Dungeons series are clear inspirations, but what do you feel Minos brings to the genre that players haven’t seen before?

Kacper Szymczak: Actually, Dungeon Keeper being a defense-y base-building RTS of sorts, isn’t on the top of the list of the inspirations and references.

Genre-wise, the game is closer to The Incredible Machine, reversed Lemmings and Pac-Man/Bomberman.

It’s hard to tell what Minos brings to the genre because as we playtested the game, players consistently find it hard to peg the game into a specific genre.

It’s towerdefense-y, in that it displays the paths the enemies will use to approach, but it changes practically every part of the genre – the paths are freely created, traps activate once and precisely, it’s more puzzly than any TD game, but doesn’t have a puzzle’y campaign structure, and gives the player a wide arrange of traps, tools abilities and freedom to mix and match and combo in any way they see fit.

The labyrinth itself is central to the game. How do you balance giving players freedom to create wild, imaginative mazes while still ensuring the game feels fair and strategically challenging?

Kacper Szymczak: That is an excellent question, in that it is incredibly tricky to maintain the balance of Minos.

The core of the balance revolves around the economy and the number of traps at player disposal at any given time, shuffling them up, and making sure any subset can get the job done, although making it work is where the challenge lies.

The second key part is providing the player with the means to adjust the pace at which they progress through the game. Players differ vastly in their capabilities, previous gaming experience and so on. The solution lies in providing the player with means to pick a tougher challenge if they feel they can pull it off, and ensuring it’s rewarding if they do.

Lastly, the reason the game is roguelite and not roguelike, is that I’m a big believer in accessible difficulty; if a player doesn’t have the capacity/skills/energy to push through demanding challenges but does want to experience the game in their own way, I’m perfectly fine to give them a grindy way through.

Roguelikes thrive on replayability. How did you approach designing traps, artifacts, and enemies so that no two runs feel the same?

Kacper Szymczak: It’s based on two mechanisms – the push, and the pull.

Firstly, the game revolves around Artifacts you pick up during the run and the trap upgrades you chose. You have to utilize both, since early-game tools won’t work on mid- and late-game enemies. Enemies, level modifiers and other circumstances lock out specific tools the player might use, pushing them to adjust.

Secondly, tools at player disposal provide synergies with other tools and situations, pulling the player to try new things to use what they have effectively.

Shout out to our friends at Eremite Games (makers of Against the Storm) who playtested MINOS and shared this extremely valuable insight!

In most dungeon management games, the player is an unseen overlord. Here, you are the minotaur. How does that shift the gameplay experience?

Kacper Szymczak: First off all, I believe that every game tells a story, even if it’s not explicit about it.

Second, I believe that the cinema rule of “show, don’t tell” has a gaming equivalent of “make them play, don’t show”.

And so it’s axiomatic that a player should always have some character in the world of the game (even if not present in the scene or visible in the camera) whose agency grounds the story.

Having the Minotaur in the maze, at the beginning, caused nothing but trouble.

Since our goal is to make a maze designing game, controlling a powerful beast naturally gravitates the experience towards a dungeon-ey hack’n’slash while in control of a cow-like Predator.

It was (and is) very tricky to have the player feel the Minotaur is powerful, but at the same time not have them constantly use him for direct combat. It’s all about finding ways and giving the player tools to do things that are more effective than direct engagement in battle.

To give you an example, there’s an ability that lets you smash walls, as a means of escaping a tough situation. There’s an artifact that makes the smashed wall explode, causing damage to nearby enemies. So smashing a wall into a group of unsuspecting invaders is far more enjoyable (and effective) than waltzing into direct combat. Therefore, it’s elements like this, helping us help the players help themselves to play Minos in a more fun way.

Minos lets players decide whether their labyrinth is “clever or cruel.” Do you see morality or tone as part of how players express themselves in the game?

Kacper Szymczak: It’s always quite cruel, but it’s worth noting that Asterion (the Minotaur) is not a villain character, but a protagonist. He’s as evil as Home Alone’s Kevin.

The game tells a tragic story of a boy cursed through no fault of his own, invaded and hunted out of greed and hatred. It is a story of solitude, of being cast away for being unlike your peers, of finding inner peace through self-acceptance despite one’s flaws.

And traps being cruel, savage and murderous is merely an extension of the universally appreciated castle doctrine.

From a design standpoint, what was the hardest part about blending puzzle-like construction with real-time defence against adventurers?

Kacper Szymczak: Why, the time-space continuum, of course!

The maze is based on a grid, and the key factor is location – enemies being on a trap, in line of fire of a ballista, enemy being behind a closed door, enemy on path to a lure. And all this works fine, and allows for deterministic decision making, planning and fruitful and satisfying execution.

Not all things can be crammed into the space dimensions; some are strictly tied to time. So enemies on fire are burning for a given time until they’re fragrant and crispy, but where does that burning duration end is an endless balance issue and a UX struggle.

On the plus side, the time-related gameplay elements flesh the experience out with a sense of simulation and a drop of unpredictability/unwieldability, which prevents the game from being all about careful calculation. Circling back to the previous question about the presence of the Minotaur in the mix, when things go south and work out exactly as expected, it gives room for the player to roll out the beast and wipe the remaining enemies, which ties things up nicely and in a rewarding fashion.

Your studio Artificer is known for games like Showgunners. What lessons from those projects influenced how you approached Minos?

Kacper Szymczak: These are two drastically different games and the lessons drawn from Showgunners seem so dated as if they were learned a lifetime ago; every so often as I look back at the designer I was, I consider the past me an utter idiot and an incompetent buffoon.

On the plus side, it reassures me that I am growing and learning and metamorph into a better version of myself.

On the sucky side, it stands to reason that in some time the current me will be judged by future me as an unbearable moron.

That being said, here’s my favourite lesson from MINOS, for MINOS. Since I like to boil complex issues to their very core, my principle on depth and creating synergies is this:

Almost all depth and synergy building in games boils down to “IF … THEN .. “ gameplay effects, but often written in a far more obscure manner for effect. changemymindmeme.jpg