Review by Matt S.

Review by Matt S.

If anyone ever again argues with me that games can’t hold literary merit, I’m going to point them to Danganronpa. Spike Chunsoft’s visual novel is very much like the original Saw film that heavily inspired it; what could have easily been a standard horror narrative reveals itself to have more layers than rings on an ancient tree and becomes a story experience absolutely essential for anyone that cares about good narrative. Danganronpa is ultimately the richest game narrative I’ve experienced in some time, and it’s a game I’m going to need to play through a couple of times to fully comprehend its full value as a work of storytelling.

The publisher, Nippon Ichi Software America (NISA), has asked that we don’t spoil the plot beyond the game’s first chapter, and it’s a fair enough request to make as the game does have twists and turns that work best as a shock when first experienced. So out of respect for the publisher this review won’t feature spoilers, and I strongly recommend that people do not seek out spoilers prior to playing the game themselves. What I can do, however, is explain how the game is set up, its narrative structure, and then explain why the game is the greatest melting pot of philosophical concepts that I’ve come across in a game to date.

The basis of Danganronpa is built on game theory – an economic theory that explains more about human behaviours and motivations than many of us would like to consider. To narrow down how game theory works to a basic example, people often cite the Prisoner’s Dilemma, of which Wikipedia provides a fine summary:

The basis of Danganronpa is built on game theory – an economic theory that explains more about human behaviours and motivations than many of us would like to consider. To narrow down how game theory works to a basic example, people often cite the Prisoner’s Dilemma, of which Wikipedia provides a fine summary:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of speaking to or exchanging messages with the other. The police admit they don’t have enough evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They plan to sentence both to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the police offer each prisoner a Faustian bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other, by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. Here’s how it goes:

If A and B both betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison

If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa)

If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge)

Now, according to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the best outcome for both people is for both to remain silent. But if one prisoner chooses to betray while the other remains silent, the proactive prisoner will benefit more, and essentially “win”. So based on what we know about human psychology, the temptation to betray the other prisoner is almost overpowering. Game theory is, in other words, a model that accounts for human greed, making it a useful way of thinking about business and economics, but also of social interactions between people.

Naturally the atmosphere among the imprisoned students quickly sours into one of suspicion and paranoia, and inevitably some of those students fall to the temptation to make a play for freedom. The deadly game thus begins.

Danganronpa’s plot has been seen often enough in other recent films, books, and games. Whether your poison is Saw, or Battle Royale, or The Hunger Games, or indeed other games such as Virtue’s Last Reward, game theory is a popular topic in narrative at the moment. There’s a good reason for that popularity; Game Theory gives us an deep insight into humanity itself. There’s an animalistic self-serving part of the human spirit that can never be dismissed, though often we’re called on to repress it. Or in Danganronpa’s case; every one of those 16 students wants to be free, but in principle they also want to bond with one another and engage in building a civilized society. Seeing how that tension plays out is fascinating, and oddly emotional; as players we’re asked to sympathise with the murderers, and connect with the victims and as a consequence it’s impossible to ever feel certain of what’s going on in this high school.

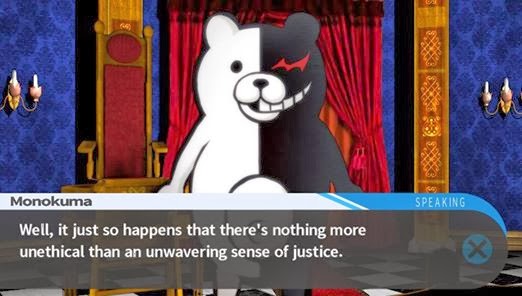

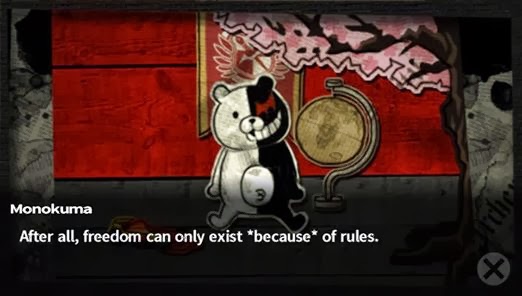

As for the rules of the school itself; those are administered by a creature called Monokuma; a talking (robotic) bear that is responsible for the student’s imprisonment. This bear is an odd series of contradictions himself; though clearly a force of evil there’s a noble streak that runs through Monokuma – he slavishly adheres to his own rules and is, ultimately, looking to expose an evil that runs through humankind itself. Never does Monokuma insist that one person kills another. He encourages it but ultimately it’s the individual’s choice to go through with the crime, and so, just like the villain of the Saw films, Monokuma can be seen as much as a mirror to humanity and a temptation to do evil than a cause of evil himself. He’s an oddly honest personality and, in many ways, admirable as a result.

The students of the school (titled “Hope Academy”, for a very good reason that is later revealed), meanwhile, are all literal personifications of personality types. In a similar vein to virtue names, each character is the “ultimate something” – the ultimate athlete, the ultimate wealthy elite, the ultimate pop idol, and each of these characters reflect their personalities. As with virtue names when used in literature, the game uses these “ultimates” to reflect various facets of the human condition, and the interplay between the various character types is really quite fascinating. Can the wealthy elite come to terms with the need to work with those that his people would exploit? The pop idol is too adorable to possibly be guilty of anything, right? And, is the ultimate lucky individual truly lucky? These questions about each character’s personalities and motivations will have you constantly second guessing yourself; the true hallmark of a classic mystery story.

Subtlety might not be Danganronpa’s strong point, but the characters are fascinating and Monokuma is one of the finest villains ever written into the game so I quickly forgave Danganronpa for treating me a little like a simpleton. At around 25 hour’s length, Danganronpa has the narrative depth of a good short story.

The game itself is, like most visual novels, quiet straightforward. Players navigate through an environment gathering clues based on what the game instructs them to do next. Once all the clues have been gathered it’s time to go to court and use those clues to present as evidence. This takes the form of a variety of minigames, from spelling out words in a hangman-style game, to tapping on specific clues as they float up on the screen hidden among red herrings, to a weird rhythm game. While a player can fail these courtroom scenes by performing badly at the minigames, the narrative itself plays out on rails. I would have really loved if the game allowed me to find my own clues rather than follow the narrative breadcrumbs, and it would have been great if I was expected to come to the conclusion of the guilty party rather than have the game simply announce it once I’d successfully completed all the minigames, but then I remind myself that this is ultimately a visual novel.

Away from the court scenes there is some player freedom in terms of forming bonds with the other students and learning their back stories. It’s just enough to create the illusion of interactivity and player choice, without actually providing players with any way to deviate from the main plot line. Once the main story is finished, Danganronpa opens up a rather wonderful light management sim, which is ironically more of a game than the “main” game, though it also lacks the emotional and intellectual depth.

At its core, Danganronpa is a melting pot of various philosophical puzzles that pulls together in such a way that it connected with me on a very deep, very real level. Without giving the ending away, the ultimate fate of all the characters (including Monokuma) left me more than a little shaken, and any game that’s able to connect with me at that kind of primal level must be worth the investment.

In short, Danganronpa is a strong contender for my favourite game ever.

|

| (That’s 5 stars, for the record. An emphatic 5 stars) |

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld