Retro reflections by Nick H.

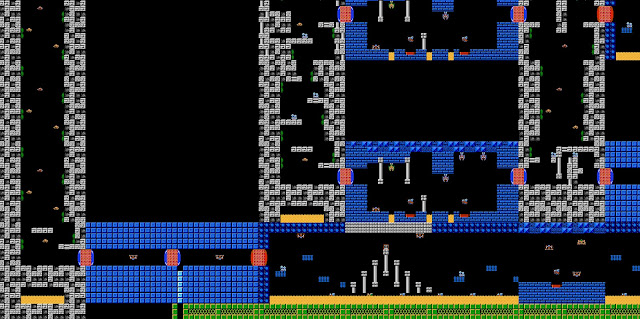

Having spent a good deal of time with Dark Souls III recently, the idea of good level design has been forefront in my mind. This led me to dig up my copy of Metroid, a game that I first played about a year after its initial release. I was happy to find that the game still holds up amazingly well today, but it also reaffirmed many of my notions about its level design as well.

There are a lot of classic games that stand out for having done something that was ‘first’ in my experience, or particularly memorable for doing something I had not seen done or done so well before. Metroid stuck with me after the first time I played it because of how creative the level design was. As soon as I had finally beaten it, I played through it again just so I could experience it knowing what I had learned about it along the way.

To read on, log in to your DDNet Premium account: