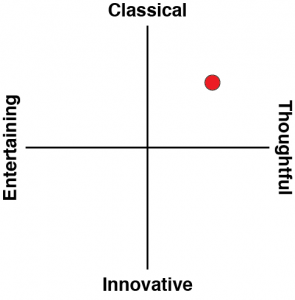

It would be easy to dismiss Monochrome Mobius as being a “too-traditional” JRPG, turn-based warts and all. Indeed, that is what far too many other critics have done when covering this game, and that’s doing it a disservice. It seems that just about everyone has missed what makes this a really rather special, if humble, storytelling experience.

Related reading: Our review of Utawarerumono: Prelude to the Fallen.

Monochrome Mobius is a prequel to the previously released Utawarerumono series. No, you don’t need to have played those later games, but as several characters do show up (including the protagonist himself) in later titles, it also helps to know who they are beforehand. For anyone who has experienced the Utawarerumono series, then you may well know that, in an almost unique twist, this series is explicitly inspired by Ainu aesthetics and traditions.

The Ainu are a native people to Hokkaido and while they’ve had an unfortunate history (including way too many efforts to completely stamp out their history and heritage), they have a wonderful culture with an entirely unique sense of dress and tradition. It’s just one that is incredibly difficult to learn anything about, particularly when you’re trying to study it outside of the Japanese language. Utawarerumono and Monochrome Mobius won’t do any more than inspire you to learn more about where its unique vision comes from – it’s by no means accurately retelling Ainu stories or history – but at the same time, there’s enough there to pique the interest, and I sincerely hope it does inspire that response, because the Ainu are a fascinating part of world history, and this game series helps to familiarise it on some level for players.

Like most native peoples, the Ainu have a rich storytelling tradition, and it’s relayed through oral traditions such as legends and song. Perhaps the thing that I found most appealing about Monochrome Mobius is the sense of just that coming through it. The party of heroes need to learn songs and decipher legends on their way to understanding what’s going on (and it’s a doozy of a fantasy with a lot going on). Meanwhile, they are building their own living legends through their exploits, as we then see in the later Utawarerumono series. Where those games were true visual novels, with Fire Emblem-like tactics combat really serving as a break between hour-long story segments, Monochrome Mobius is a more traditional JRPG with traditional cut-scenes and a storytelling structure.

Frankly, that shift from VN to JRPG means there’s not enough of it. The team of Aquaplus have amazing writers and they’re working with sublime characters, and every cut scene adds something to that characterisation. Personalities are well drawn, and there’s a good mix of humour and the more serious fantastic drama to keep players captivated. However, in comparison to a visual novel, there are naturally storytelling concessions made, and if there’s one failing in the storytelling found in Monochrome Mobius, it’s that there’s just a little too much effort put into using story segments as utilitarian opportunities to keep players following the trail of breadcrumbs.

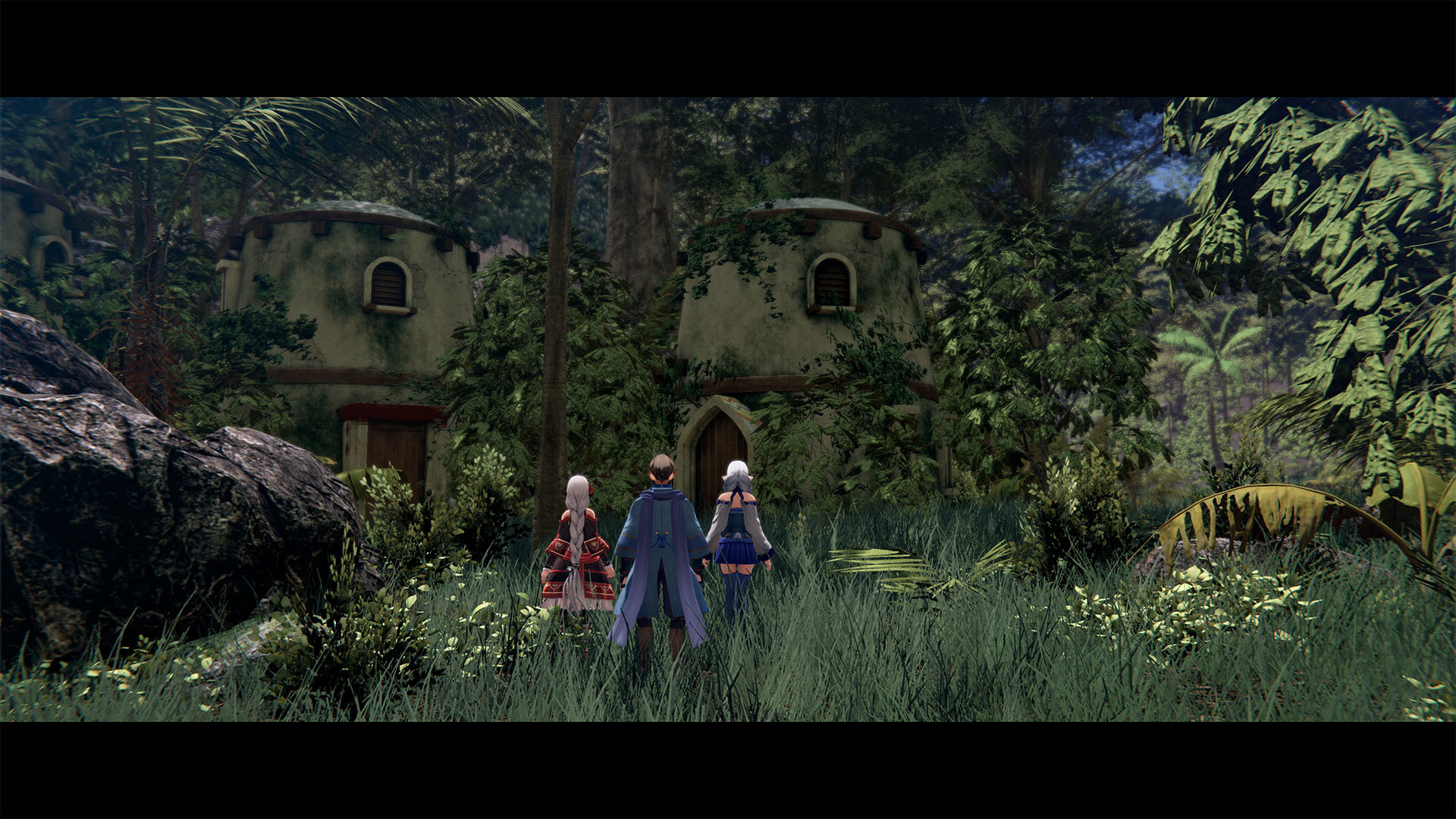

Thankfully, the decision to design a traditional JRPG is more than validated by the world design itself. While Monochrome Mobius is not an open-world game, the environments are massive, winding, and full of intriguing secrets and treasures to find along the way. Because the turn-based combat is snappy and nostalgic (a great thing for people that do enjoy traditional JRPGs), the rapid-fire rate the world throws combat at you isn’t so much a drag, and because there are only around 30 or so side quests across the entire adventure, you never find yourself backtracking enough for exploring any part of the world to become tedious. You’re constantly moving forward in this one, and that’s the right approach for JRPGs to take.

In battle, every character has their own specialty, and set of skills. About the only area where Monochrome Mobius breaks away from the formula established right back with the original Dragon Quest is the “ring” system. In the top corner of the screen, you’ll see a series of rings with an icon representing each combatant placed on it. Those rings rotate between attacks, and when an icon reaches a certain point, it’s that character’s turn to attack.

That in itself behaves no differently to a typical ATB battle system, from as early as Final Fantasy IV. The difference comes from the ability to move up and down the rings. If you’re on the inner ring, you’re going to spin around for a new turn much more quickly than a character on the outer ring. Meanwhile, if you’re able to knock your opponent into an outer ring, then you’ll have a further advantage over them. This isn’t the most tactically complex or exciting iteration of stock-standard turn-based JRPG combat that we’ve seen, but it also doesn’t need to be. It’s entertaining and gives each character the opportunity to shine in their own way. Sometimes traditional gameplay mechanics, when put in the context of a game that is otherwise refreshingly different and differentiated from its genre peers, is a perfectly acceptable way to go. It highlights that the developer understands that, JRPG or no, it’s the characters and worldbuilding that’s the main draw of this game, so why try and shift focus by having people concentrate too hard on battle?

Further assisting the game’s ability to draw you into its world is the presentation. Monochrome Mobius was made on a budget and it shows in places. Less significant characters often have very simple texturing, and look blocky, like they are high-resoluion PlayStation 2 characters. Environments, likewise, have corners cut in non-important areas.

However, the art direction is impeccable, and this is a beautiful game with a strong aesthetic, and artistic vision. Making progress was delightful just to see what was coming up next, and it is supported by a soundtrack that has a vague blend of tribal, natural environment and lore-telling qualities that support both the aesthetics and what the narrative is doing.

With most JRPGs – or any other kind of game, really – when I love the experience my penultimate comment will be the one or two things that miss the mark slightly. That’s not to highlight “problems” with the game so much as to highlight just how compelling the experience is, that these little irritants are all that the developers have got wrong. With Monochrome Mobius it’s easy to see the one glaring “fault” – that this game is perhaps the most traditional JRPG since the genre traditions were established – but in this case I don’t see that as a fault. This isn’t a case like Sea of Stars where the game is so slavishly in homage to everything that’s come before that it lacks a meaningful identity of its own. Monochrome Mobius is just as traditional, but confident. It has its own personality, its own themes, its own message, and its own characters, and it’s not afraid to let that be the quality that the game stands on. This is a far better way to handle the traditional approach.

The expanded Utawarerumono franchise might never elevate beyond the most niche of niche properties, but it is a wonderful, positive contribution to video games, and Monochrome Mobius continues translates this from a blend of visual novel and tactics to a traditional JRPG with complete success. This is a beautiful, heartfelt and sweet little game that, at around 30-40 hours, doesn’t outstay its welcome. It also reminds you that sometimes a determination to tell a good story really is better than AAA-blockbuster production excesses and flashy and overly complex gameplay gimmicks alike.