Review by Matt S.

One of the first films I ever studied seriously – back when I threw myself into film studies in the hope that I could become a filmmaker – was Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s such an influential, genius film, and I’m sure I’m not the only one that has ended up pulling that one apart in film studies. And yet, for all the influence of the film, it has taken this long to have a game come along that has been inspired by it. Thankfully we have one now. It’s called Observation, and it does the source of inspiration justice.

Observation doesn’t quite have a line of such quotable power as “I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that” – the almost Shakespearean quote we look forward to every time we watch 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet it treads over that exact same themes: the abject terror of being in space, relying on an AI, and having that AI decide to operate in an unexpected manner. Where the likes of Terminator and The Matrix were the kind of overt, in-your-face warning against unchecked AI, 2001 has always been the more subtle, realistic, and therefore terrifying application of that idea. The chances of the computers of the world waking up and turning into a Skynet-like menace are minimal. By contrast Kubrick was nearly prophetic. We’re already almost at the point where we are so reliant on computers that a computer deliberately “misbehaving” for one reason or another is a terrifyingly realistic prospect. This is the kind of AI that Stephen Hawking was concerned with. Hawking was never wrong. That was kind of the point.

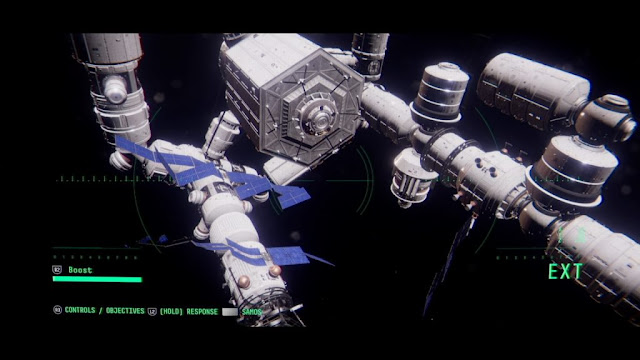

Observation is particularly interesting, because unlike in 2001, where you’re sitting back and watching, here you’re playing as the technology. Events kick off when an unknown disaster befalls a space station. Waking up, a woman astronaut (Emma) can’t find the rest of the crew, and needs to work with you – an AI called SAM – to put out the immediate (literal) fires threatening her life, before trying to figure what has gone on – and what is going on in front of her. Those things get really frightening when you look outside to see Saturn. You were meant to be hovering around Earth, and now you are far, far off course. What’s worse, there seems to be a part of SAM that’s responsible for all of this – a sinister part that neither Emma – nor the rest of SAM (the part you play as) are really aware of.

Immediately, SAM becomes one of the best realised examples of the unreliable narrator we’ve seen in video games. As SAM, you need to help in trying to solve the mystery, and the safety of everything on board the space station, but at the same time, some part of the program is conducting actions that seem to be in direct conflict with those goals. Just what is the purpose of SAM, and why is it doing what it’s doing (if it’s actually doing it at all)? It’s rare that a game asks you to question the motivations of the protagonist that you’re in control of, and yet that’s what Observation does. On top of that, it comes across as all the more intense precisely because it’s all playing out in first person, with you sharing the exact same viewpoint as SAM. The layered sense of mystery at the heart of Observation – what’s going on, what’s SAM’s role, and why are there odd messages that keep popping up in Sam’s interface like “bring her here”? – all combine to give a strong sense of foreboding, sinister mystery, which makes the controller incredibly difficult to put down.

Mystery stories set in space always have that element of fright, and while Observation is not a true horror game in the purest sense, it certainly does a great job in establishing fear. Consider the great hallmarks of horror – isolation, a persistent sense of threat, a lack of agency, and mortal consequences. The act of being in space has all of those themes on a fundamental level. Space is frightening. You’re essentially on your own, the hostile vacuum of space is constantly trying to kill you, and the tiniest mistake can mean death. Up there, a little fire is an existential threat, so the immediate impact of being blown far off course is the realisation that your story is probably not going to end well. Observation does a really great job of using every element available to the developers – from the interface, to the limited interactivity, through to the clever juxtaposition of the claustrophobic space station with the rare shot of the expanse of space, to slowly build the tension and drive home the idea that you’ve got so little control. You don’t even really control your own character, because, again, SAM’s constantly being compelled to do things in direct opposition to what, you assume, is for the good of the space station.

The limited “gameplay” in Observation strengthens its themes. As SAM, your primary ability is to “jump” from camera to camera, at which point you can look around. Much of the time you’ll be asked to “spot” things – where a fire is coming from, for example. Or what’s going on outside of the space station. At other times you’ll need to manipulate the technology – inputting codes, or solving simple puzzles to turn on power generators and the like. Constantly, however, you’ll be left feeling like much of what’s going on is not in your hands… even putting aside SAM’s apparent other self, you’re constantly reminded that you are playing as an AI that serves at the beck and call of the crew, and really, all it can do is follow orders.

It you’re not interested in delving deep into the commentary that Observation offers on the dangers of AI, the unreliable narrator, or how the developers have carefully stitched together a game with the same sense of the surreal as Stanley Kubrick’s film, you can still enjoy this one for the ripping yarn that it tells, with the superb performances at its core. It works every bit as well as a simple thriller in the vein of Gravity, thanks to the sense of tension and stress that it builds. It’s also quite the cinematic experience, with the developers showing impeccable research on the design of space stations, and an incredible sense of awe at space itself, when the camera jumps to outside of the space station.

The one thing I was not a fan of was the monster sub-plot – or at least the notion that there’s something else on the station with you. It does add to the mystery and sense of Observer being a thriller on the one hand. On the other, it undercuts the tense psychological games that the game plays, and the narrative around the (potentially) psychotic AI. This too has precedent within cinema, with a number of otherwise excellent and tense science fiction thrillers being let down when a mundane “monster” shows up – the most perfect example of which is the mostly brilliant, but ultimately ruined, Sunshine. I’m not sure if writers don’t have the confidence in giving audiences science fiction without a physical antagonist (or, at least, a clunky potential of a physical antagonist made manifest), and struggle to trust audiences to “get it,” but there’s a common thread across much of science fiction that a tight, psychological narrative also needs the arbitrary monster. Observation handles it better than most, but I’d still argue it never needed the ‘there’s something else here with us’ moments.

I will also say that as a game, Observation has some issues that might detract from it for some people, though those same issues are essential to the game from a thematic perspective. Puzzles don’t tend to be particularly well explained, and while you generally have all the time that you need to figure your way through (and it makes narrative sense that there aren’t markers and “game-like” guidance), for many people the pacing of the game is going to slow when one puzzle or another sticks them. On the other hand, with such little hand holding, there’s a strong sense of satisfaction that comes from working through the game on your own initiative, and on a more unconscious level, feeling a bit confused about how to play (and what to do next) really fits with the uncomfortable mysteries that sit at the core of Observation.

We don’t get many games that aspire to be true and honest works of art, but Observation is one. It’s easy to dismiss as being too heavily in homage to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but that would be doing it a disservice. It makes excellent use of the tools afforded to game developers to also reposition the player in relation to the narrative, and deliver that deadly relationship between AI and humanity that was at the core of 2001 in a far more intense, even visceral manner. Observation is truly a thinking person’s game… and it’s a rare gem for that.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

Please help keep DDNet running: Running an online publication isn’t cheap, and it’s highly time consuming. Please help me keep the site running and providing interviews, reviews, and features like this by supporting me on Patreon. Even $1/ month would be a hugely appreciated vote of confidence in the kind of work we’re doing. Please click here to be taken to my Patreon, and thank you for reading and your support!