Feature by Matt S.

Goichi Suda is a bit of a hero to many on the DDNet team. His unwavering commitment to games that are transgressive and creative, even to the detriment of their critical rating, is noble, and the fact he’s managed to build up a major Japanese development studio almost entirely around him shows that he’s both a visionary and a leader.

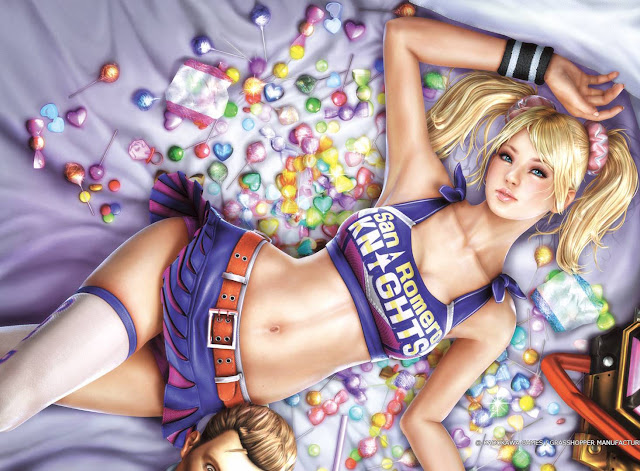

Related reading: A look back at Lollipop Chainsaw and its subversion of the sexist cheerleader tropes.

Over the next few weeks, through Tokyo Game Show and beyond, we’re going to do an extended series of feature articles, where we look back on various games that Suda-san has been involved in, and detail what makes them significant and unique to Suda’s vision. Further, we’re also going to feature interviews with various other creators that have worked with Suda over the years… and that’s all leading up to my third meeting with the man himself at Tokyo Game Show this year. I hope.

These articles are premium articles, but courtesy of the good people at Playism (who are handling the long-overdue port of one of Suda’s first games, The Silver Case), we are able to give all readers full access to each of the articles.