Inescapable: No Rules, No Rescue is not the Danganronpa clone it seems to be. It looks the part, but rather than being a “death game,” it’s closer to the first 90% of Lord of the Flies (the part where there’s tension but no murder) than Saw. Or Blue Lagoon were it an orgy rather than a single couple. In fact, it’s just as well that it’s not really a death game, because the success of Danganronpa and its ilk rests on how well you like the characters. In Inescapable I would have fed almost all of them to Monokuma machine about ten seconds after hearing them speak for the first time. Punishment be damned, I’d want off this island.

Seriously. There are very few likable characters in this game. There’s the “OMG, like lol whateverrrrr,” zoomer valley girl, and she’s pulled directly from the textbook of “everything that people hate about Gen Z.” There’s the old Italian dude (who is also a truly raging bigot), the aggressively sullen non-binary that seems designed to confirm every negative stereotype the bigots believe of them, the Swedish maid (no, really, that’s her entire personality), the protagonist himself (who can come across as wildly misogynistic) and Mia.

Yeah, okay. Mia’s the exception. I really, really like Mia. Were this game fully aspirational, I’d knock off all the other characters and then Mia and I could really live out Blue Lagoon. But then she could do better than the protagonist and wouldn’t really deserve that. You play as Harrison, and for the aforementioned reasons, Harrison doesn’t do the reputation of the people of the UK any favours.

If you can put aside the characters, the situation that they’re in is a compelling one. This group of characters has been kidnapped and imprisoned on an island. Anyone who survives there for six months (while making things interesting) will “earn” $500K. Unfortunately, because every single one of the characters is a total caricature – at least, at first – it’s hard to care enough about any of them to want to see them to the $500K.

Related reading: Australia’s own Danganronpa clone is the excellent Quantum Suicide. Our review.

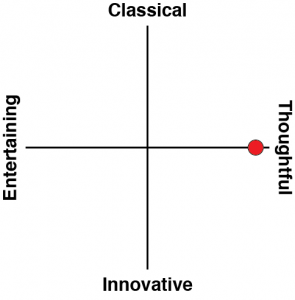

Why the characters are such caricatures is clear enough from a thematic perspective – they each represent some kind of quality within society, and then the moral and ethical questions that get posed through the game play out as a discussion about that attitude or behavioural quirk with the real world. For an easy and obvious example; the bigoted older guy and his attitude towards non-binary people is meant to be an examination on how people do perceive non-binary people in the real world. Or, as this academic paper by Alireza Isfandyari-Moghaddam puts it: “Caricatures can illustrate the sufferings of citizens by tackling the issues of the society, analysing economic problems, and analysing problems. Political caricatures can make help oppressed people by criticizing the status quo and unjust political practices. Caricatures can deal boldly with social problems because they can escape censorship.”

Danganronpa itself makes great use of caricatures that, within the game’s fiction, are given literal form. Each character is the “ultimate” something-or-other – a caricature construct that, in the context of that game, makes the interactions between the characters a fascinating microcosm of broader society… which in turn lends the death games an intense dynamic.

The problem with Inescapable is that it’s just not written well enough to do these themes justice, and because caricature, done poorly, is too exaggerated to command attention or respect, it’s far too easy to simply laugh at these characters for being either stupidly nasty, stupidly silly, or just plain stupid.

Now, with all of that said I will add that Inescapable gets better deeper into it. This is an extremely long game, and it features a lot of conversations and scenes that don’t seem to add anything directly. What they do, however, is slowly get their hooks in. Very subtly the characters start to shake their initially single-faceted personalities to become something more. It’s not enough, and the phrase “slow burn” does not even begin to describe it, though. Inescapable takes so long to arrive at the reason why you should care for the characters that the chances are that by the time you get there, you’re not likely to anyway. But, for those that persevere, the third act of the game does give you strong revelations about the characters and their situation, and shares a much stronger vision for what the overall experience was meant to be.

Beyond the characterisation I do think the developers went into Inescapable with some grand ideas of making A Lot Of Points, though again, because they’re not particularly great writers, these all play out without really being as impactful as they should have been. The big one is the idea that you’re meant to be trapped on an island for the entertainment of a bunch of people watching in. You’re told that if you don’t make things interesting enough for the audience, everyone on the island will be punished. This could have been a grand criticism and satire of the voyeurism of modern entertainment, except that the developers really struggled to make it compelling, and you’ve got to go all the way back to Manhunt on the PlayStation 2 to find the video game industry’s best take on that particular social commentary theme. Or you could just watch Squid Game or Battle Royale again.

For all the above, the one thing the developers really nailed – pardon the upcoming pun – is the horniness. Inescapable’s setting – and I again reference Blue Lagoon because you can’t help but see it – means that a group of young hot adults are now uninhibited, and this is played up to the maximum. This crew has incredible thirst. Of course, when the horniness involves Zoomer’s worst valley girl or the Swedish maid cosplayer, it’s more akin to torture than pleasure… but then there’s Mia. Oh yes, I do appreciate the game’s tacit approval for getting thirsty for Mia.

Related reading: The team behind Danganronpa went on to may Rain Code. Our review.

For a game that is desperate to be seen as sexy, Inescapable’s art is… bothersome at times. It can look good, particularly in the cut scenes and those times where characters are wearing less clothing, but then some of the sprites and their reactions seem a little amateur and over-the-top, even for caricatures. I did, however, appreciate the diversity at play. The developers really did try to show us how sexy a broad range of people and across the eleven characters, there’s a design in there for just about everyone.

The game offers multiple endings based on your decisions along the way. The problem with doing this in this kind of game is that you’re meant to make decisions based on your own moral guidance. However, the way the game is designed also means that to see all the endings, you need to remove yourself from the experience by specifically choosing things you find incorrect, uncomfortable, or even downright vile. It takes a very, very special game to actually incentivise that. Disco Elysium’s pretty close to the only one I can think of (that game did such a good job of being academic and smart it convinced me to play the fascist route just to see how things pan out). Inescapable, though, is just not that well written and the incentive to replay to see all the endings is particularly low. The various minigames it offers do make up for the conceptually flawed “gameplay” in the decision-making, though. There’s a mini-arcade on the island to enjoy. With a lot of downtime, I did spend a lot of time hanging out there.

There’s so much to like about Inescapable. The concept is solid and the developers seem to have had the right intentions. The vision is there. It’s also horny as anything and why the heck not? We don’t really have a Danganronpa-like that made the obvious observation that a bunch of super-hot young adults, trapped in a kind of “paradise,” are almost certainly going to get it on. It’s just unfortunate that this is a 15-hour game that takes about 10 hours to start getting to the point, and from start to finish it’s simply not written well enough to demand the player sit through that.

Thanks for reviewing this. At some point I was going to pre-order, because I sensed a lot of the fun aspects you outlined in the review … but once I saw some gameplay and learned that the characters all seem to be either unlikable or downright grating, I took it off my list. Hopefully for the developers, there will be an audience who enjoys these characters.

Yeah, I was really disappointed because from the screenshots it did look like something I would love, and this is the first “death game” that I’ve only enjoyed, not *loved*.

Ah well. Not every game can be Danganronpa 🙂