In some ways, the success of NieR: Automata has cursed Yoko Taro. Following the profound success of that game, people now expect him to be subversive and deep, sharply funny and wildly creative with everything that he touches. Voice of Cards: The Isle Dragon Roars is not NieR. It’s a more subtle and restrained Yoko Taro, but it’s also a narrative and storytelling experience with few peers.

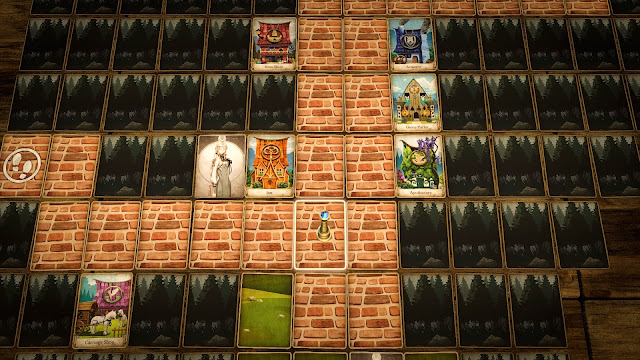

The quirk in this game is that everything is a card. The map is a “board” with every space being a card. During cut scenes your characters are represented by cards, and they tilt and slide around to simulate actions like bowing, fighting, or walking. In combat, every item and ability is represented by a card, which you play onto the board to attack your opponent or heal your allies. This aesthetic and interface, coupled with the story being told entirely by a Dungeons & Dragons DM-style narrator, gives the game a flavour all of its own. The storybook tone that it strikes also supports the plot itself, which comes from a very Grimm-like place. For example, one of the early story arcs features a woman deeply in debt, who acquires a flute that is meant to bring good fortune, but has a disasterous effect. See? Very Grimm.

While that narrative goes to some very dark places, it is a Yoko Taro game, so it goes there with a sense of humour, too. One of my favourite things about Voice of Cards is the way that, after defeating a certain number of the same monster or encountering certain people, you unlock little background stories about them in the game’s gallery. Now, I so rarely delve into the gallery of video games, but I couldn’t help myself with Voice of Cards – the stories were only ever a few lines long, but they were almost always brimming with personality, style and humour… and many of them offered quite a surprising little anecdote, too.

Though Voice of Cards does look like a card game, it is in execution a complete and “proper” JRPG. The party moves from town to town, completing little quests in the pursuit of the big end goal (in this case, fighting a powerful dragon). They’ll regularly delve into dungeons, filled with treasure and danger, they’ll fight random encounters and bosses, and they’ll get experience points, level up, and acquire new skills. You’ll buy the party health potions and equipment in town, and stop to rest at inns to recover. It is a complete JRPG system, however it looks in the screenshots.

What the card interface does do to the experience, however, is streamline it significantly. It would not have made sense for characters to have access to dozens of different abilities (too many cards to flick through), so instead Voice of Cards limits you to a couple of different abilities per character, chosen from a relatively thin range of abilities that they slowly unlock as they level up. Likewise, there are no complex skill trees to manage, and equipment is limited to a couple of pieces per character. Mechanically, Voice of Cards behaves very much like the early era Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest, which also speaks to the nostalgic wash that Yoko Taro and the team have tried to convey.

Unfortunately, there is one issue with Voice of Cards: It is ridiculously easy. Towards the end, there are a few battles that will challenge you, but that really is only a few battles. Coupled with the fairly lengthy loading times and animated introduction to each battle (there’s a whole process where a board is placed on the “table” and cards representing your party and opponent are arrayed facing one another), and the high frequency of random combat in dungeons, a chunk of the pacing of Voice of Cards is undermined by battles that are too much like a process and chore. It is nice delving into a new area and seeing what new enemies there are to fight (because the art on these cards is gorgeous), but the combat itself loses momentum fast.

More than anything else, though, what excites me most about Voice of Cards is how modular it could be. I don’t know if this is the plan that the developers have in mind, but the way that Voice of Cards is structured, the base game here could be a platform and foundation, telling many stories and featuring many characters, parties, and world-shaking events layered over the top. Where most JRPGs follow a single group of heroes and the experience is very much centred on them, the way Voice of Cards is designed makes it feel as though the world itself is the “protagonist” and the story of any individual party is just sitting on top of that.

In fact, we’ve already seen a hint of this potential in action. The Voice of Cards demo, which was released a few weeks before the full game, put you in control of a party of heroes that become rivals and antagonists to the group in the full game. At various key points your paths will cross with them and, having played the demo, it’s hard not to let the immagination wander as to what that group is up to when they’re “off screen.”

Perhaps it’s the game’s ability to get my imagination working that is the underlying reason behind why I love Voice of Cards as much as I do. So often we expect the video game medium to supplant the imagination; we expect the cinematics, animation, character design and world design to have all the information that we need to be held within it. We talk up how interactive video games are as a unique quality to the medium, but from another perspective, in how games get us thinking and “filling blanks” it’s actually a much more passive art form than literature or music, where we need to be more active in the creation of meaning. It’s akin to mainstream cinema in that way.

Voice of Cards, however, directly aims to encourage immagination and creative thought, leaving so many blanks that the player has a great deal of agency in setting the scene. The storytelling itself is quite linear – which is a little disappointing in this context – but if the Voice of Cards concept can be expanded to encapsulate a handful of different stories, being able to see events and characters from different perspectives promises to be a rich web indeed.

So, while Voice of Cards could be refined as a game, the vision is impeccable, and while the game’s not as outrageous or subversive as NieR and its sequel, it still represents Yoko Taro’s unique qualities as a game designer and narrative writer: he is forever experimenting and pushing boundaries. Voice of Cards is almost subtle in this, but the way that it aims to work collaboratively with players to share a story, rather than tell it, is a delightful departure from the norm for the JRPG. I don’t think anyone expected him to follow up NieR with a “card game,” but Yoko Taro has hit onto something very special here.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb