Three years ago, when Idol Manager popped up on Kickstarter, and promised to give you the opportunity to manage your own AKB48-style J-Pop idol group, I assumed that it would all be something of a joke. I assumed it would be focused on fanservice, with very little serious simulation. Wow was I wrong about that. Idol Manager doesn’t flinch from anything. It’s more than happy to fail you and your idol business, and while it has got a cutesy charm and lots of pretty girls, Idol Manager also doesn’t flinch from the reality that this industry is deeply problematic, often associated with all kinds of the seediest individuals and businesses.

I won’t spend too long in this review qualifying just how problematic idol groups and culture in Japan can be, but for just a few examples: in 2013 AKB48 idol, Minami Minegishi, was forced to shave her head after “being caught” spending the night with her boyfriend (idol fans don’t generally like hearing news about “their” girls having sex lives). In 2014, an obsessive “fan” wielding a saw attacked a couple of girls, again in AKB48, at a handshake event, where men (predominantly) pay a fortune for the opportunity to touch the hand of their favourite girl. And when the groups aren’t actively encouraging every creep in Japan to become outright stalkers, they’re encouraging the most disgusting excesses of consumerism; in 2017 a man was arrested for purchasing 600 copies of the same CD, and dumped the lot of them in a forest (illegally, of course). Why did he do that? Because each CD came with a voting slip, allowing him to vote for his favourite girl 600 times in the annual “choose your favourite girl” poll. Buying hundreds of copies of a CD just to pump up the popularity of one of the members is a good way to make a lot of money for the producers, but it’s also a deeply offensive example of the obscene end of capitalism.

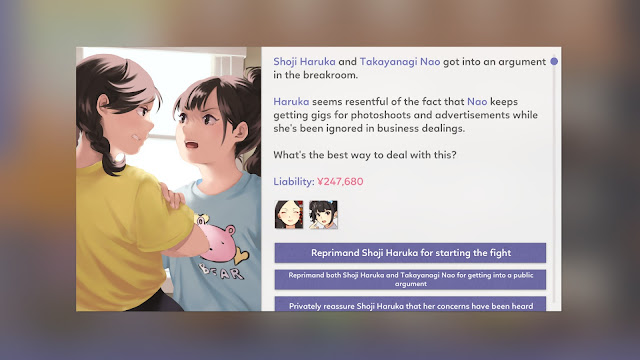

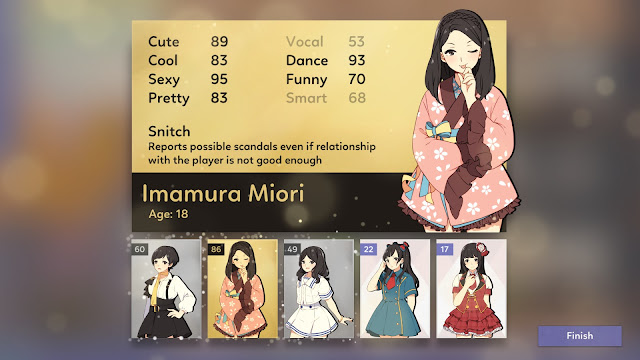

All of the above, and so much more, plays out to surprising detail and depth in Idol Manager. Idols get boyfriends, which causes scandals. Girls bully one another, or start dating each other, too, and that can have significant negative impacts on the group dynamic. They’ll get into scandals for doing the wrong thing on a live stream, and the whole group will get in hot water when politicians decide to speak out against the messaging in the music (or the “over-sexualisation” of the girls) in order to win popularity points. Mechanically, you’ve got to set dozens of rules about what girls are and are not allowed to do, and the penalties for being flexible and loose with the rules are very explicitly designed to encourage you to view these girls as resources to control, rather than people. They won’t be happy about it, but the more sociopathic you are in your managerial style in Idol Manager, the more likely it is that you’ll find success. Finally, of course, there are plenty of opportunities for sexual exploitation beyond the scandals. You can promote your group using everything from handshake events to “Lewd PV” (music video) releases, as well as training the girls to “dance sexy” to really lean into that side of idol promotion.

For all that I’ve written above, idol culture is also not all bad, since life doesn’t work in black and whites, and Idol Manager also represents the best of this industry. Idols are an institution in Japan, entertain millions of perfectly healthy, well-adjusted fans, and they’re a talent feeder that leads to any number of acting, modelling, solo artists and other entertainment career opportunities for talented girls. Idols set trends, delight, is worth a fortune to Japan’s economy, and these groups and individuals enjoy a deep cultural resonance whereby the (healthy) fans of these groups form little communities focused on helping to build up and celebrate their favourite group’s successes. There’s no direct translation to the way celebrity works in the west, and studying how the idol culture over there ticks does help you understand something about Japan. So, in Idol Manager, if you want to build a clean idol group, protect the girls from rabid fans, and be a positive influence on their careers, then that is entirely possible, too. You can get the girls to set up a popular online show, or contract your more popular idols to perform on television or model in fashion magazines. You can focus on building an audience with women and teens, too – no need to chase after the dirty old men if you don’t want to. Effectively, in Idol Manager, you really do have complete control over how you develop your group, and there are so many different ways to do it.

You’ll start out with a small group of girls, as well as a basic office, training room and recording space. At first, Idol Manager is brutally difficult, since your group has no fans (meaning you’ll be lucky to sell 100 copies of a song you create), and it’s far too easy to start haemorrhaging money on trying to get too much done at once. Moreover, you can easily burn out the girls, since you need each individual to be bringing in a lot of money via advertising opportunities and other paid spots, but they all have physical and mental stamina scores, and without a “B-team” to back them up and give them a break, they can get tired far too easily.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb