Review by Matt S.

With Saya no Uta – The Song of Saya in English – now available over Steam, I’ve got an excuse to review what is quite an old game. And write about it. There’s so much I can write about. In terms of narrative technique, the way the game works with the unreliable narrator is fascinating, the very Marquis de Sade use of grotesque sex as theme is sublime. Its Lolita themes. What the game tells us about the nature of perception. The subversion. The underground aesthetics. There are so many directions to take a discussion about this game I probably will write all these pieces, because replaying Saya no Uta has reminded me of just how Saya no Uta is a genuine, bona fide masterpiece, worthy of a lot of discussion. I’ll start with a more general review, though. Just because it’s the best place to start.

Saya no Uta is a visual novel that was originally released back in 2009. Authored by Urobuchi Gen – the same creator behind Madoka Magica, Psycho-Pass and Fate/Zero – the game is everything you might expect from the “Urobutcher”. It is a brutally dark and unrelenting vision carefully tailored to make you feel uneasy and uncomfortable at every turn. Some have chalked it up as “pornographic”, and certainly if you download the uncensored patch to replace the edited Steam release with the “uncensored” version, the game has incredibly graphic sex scenes. But pornography? No. Nothing about Saya no Uta is gratuitous. The sex is merely the sledgehammer that really strikes the broader sadistic (as in “in the vision of Sade”) themes home.

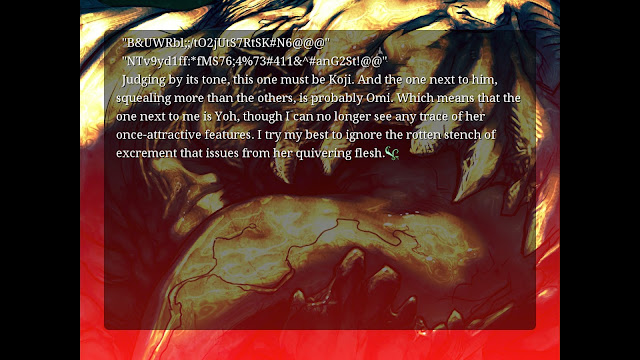

Saya no Uta follows the story of Fuminori, a college student who suffers major trauma in a car accident that kills his parents. He is only saved by a highly experimental medical procedure that messes with the wires in his brain completely. Now, Fuminori sees the entire world as a mass of rotten, rancid flesh, and every person in the world is a “flesh monster” – something so hideous and terrifying to him that he can no longer abide the world or people around him.

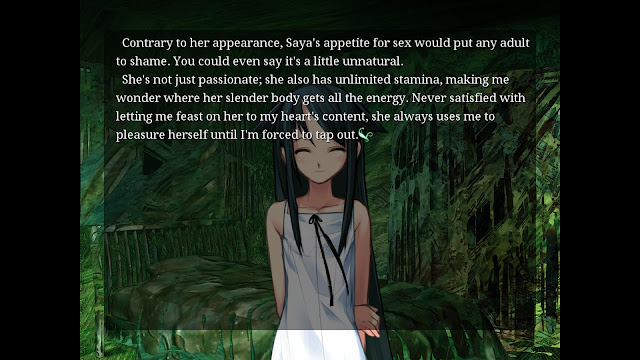

Saya is the exception. He sees Saya as a beautiful, child-like waif. Of course, she’s not. She’s actually a hideous monster that feeds on the flesh of other people, and they’re driven mad at the mere sight of her. But because Fuminori sees Saya in the way that he does, she falls for him, and they enter a passionate sexual relationship of complete co-dependence on one another.

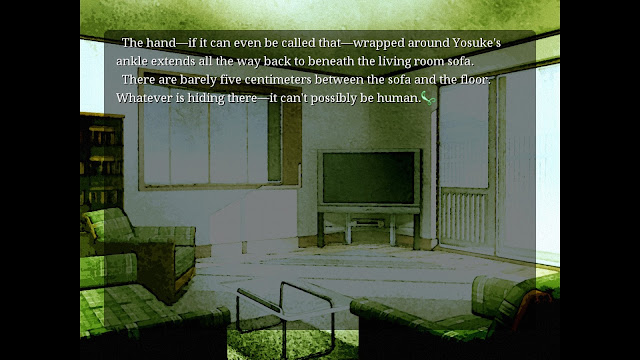

The narrative cuts back and forth between the perspective of Fuminori and those who are around him, giving you a look at both the world and the disgusting, fleshy version that Fuminori sees. The cuts between the two are used to brilliant effect. One of the most memorable scenes in this game for me was the way that Fuminori paints his home. Desperate to make the small house that he inhabits aesthetically comfortable, Fuminori and Saya mix and match colours until they finally reach a combination that Fuminori can tolerate. Then one of Fuminori’s friends, concerned for his well-being, visits the house. When we finally see what the space actually looks like, the sheer madness evident in the colours is truly shocking.

Another good example of this trick being used to good effect is the first time Fuminori comes across Saya feasting. We know exactly what she’s eating, because in the scene before we see that play out in the “real world.” Fuminori, however, only sees Saya chowing down on something that his twisted brain senses as appetizing, sweet-smelling, and delicious. We, the audience, know exactly what he is about to settle down with Saya to eat, and in a game that is often so explicit, the visual deceit here – the knowing rather than seeing – is all the more impactful. I’ve often said that it’s hard to turn Lovecraft’s vision for horror into visual mediums, such as video games or films. Lovecraft’s horror relies on the reader or audience not seeing the monster or the object of terror, and allowing the imagination to kick in and paint a picture far worse than any visual design could achieve. The places Saya no Uta allows the imagination to wander makes it perhaps the best implementation of Lovecraft’s approach to horror that we’ve ever seen in a visual medium.

Despite all the horror that Fuminori and Saya inflict on the world and Fuminori’s friends (and without giving anything away, the horror is extreme), somehow they are both very sympathetic characters. Both are victims in their own way, and while both end up being categorically monsters, there’s a kind of desperate sweetness about their relationship with one another, such that you’re positioned to wish they could just be left alone to one another. The really bad stuff is happening as a direct result of transgressions done to both Saya and Fuminori, and while the hell they inflict on the world marks them as clear villains, the victimisation of them also renders them sympathetic in their villainy.

It’s an older game now. Saya no Uta doesn’t even have a widescreen option, and as far as character design goes, the visual novel space has come a long way. Nonetheless, the sickening explicit level of detail put into the fleshy tones of Fuminori’s world makes for an enormously effective visual hellscape. Saya no Uta also makes superb use of discordant tones in a soundtrack perfectly trained towards enhancing unease.

I know people like to write Saya no Uta up as “f**ked up” or “grotesque”, and on a more primitive level, it is that. It’s not a pleasant experience by any means, and it’s not entertaining in the ways that we usually look to horror for. There are no jump scares, or random moments at all, really. Everything that happens in Saya no Uta is something you see coming a mile off. Rather than a narrative weakness, it’s a strength. Saya no Uta is horror via unease, and nothing builds a sense of unease quite like an intense anticipation for the utter horror you know is coming up.

This is a simple review. This is by no means the only article I am writing on Saya no Uta. In fact there’s going to be one every day for at least a week. As I said at the start, replaying this on Steam has reminded me of how brilliant it truly is. Saya no Uta is the closest that commercially available games will ever come to the violent brilliance of Marquis de Sade, and that’s something to celebrate for its sheer, unrestrained transgressive nature, and the meaning that it drives towards through the transgression. This, right here, is what we should be referencing back to when we talk about the artistic potential and merit of video games.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

Become a Patreon!