Opinion by Matt S.

Once developers were able to start working with polygons and creating full 3D worlds, something quite substantial happened to the aesthetics of game art. Where once, inhibited by the technology available to them, game developers were forced into highly-stylised abstractions, such as pixel art, suddenly the pursuit of realism was not only possible, but the generally positive reception that “realistic” games enjoyed elevated this to the most desirable, mass-market approach to aesthetics within games. Consequently, most blockbuster games have since aimed to provide highly “realistic” environments and characters.

Suddenly developers started to compete with one another in creating the most rounded character models, the most realistic eye and lip synching, the most flowing hair. Suddenly, sweeping, intricate landscapes or 1:1 recreations of entire cities were achievements to stick on the back of the game box. E3 became absolutely dominated by fully motion-captured athletes pulling off feats that would impress their real-life counterparts with their sheer style and elegance.

Every generation, the technology available to developers to craft these “hyper-realistic” worlds and characters becomes better. Every generation, the characters and worlds become bigger and more realistic. And all of this is a mistake. Realism in art has long been considered passe and vapid, and game developers never seem to be quite aware of just how badly they date their games by aspiring to it.

“Realism” is a pursuit that artists in other visual fields have largely outgrown. Realist art, where painters competed with one another to create the most accurate captures of the real world and its landscapes and people, is a movement that dates back to the 1850s. There were some wonderful artists who belonged to this movement, but at some point the movement became stagnant and stale, and the modernist art movement, which rejected so much of what the realists stood for, emerged. Out of modernism (and through to postmodernist movements) you have the likes of Picasso and cubism. Warhol and pop art. Dali and surrealism. Artists began to understand that by liberating themselves from the shackles of reality, they were instead able to start exploring ideas and emotions at a far greater depth; visualising things that couldn’t be seen and capturing the essence of what is really important. These days young artists might learn how to sketch people and bowls of fruit realistically, but the ultimate goal is to then turn their developing talents into more creative and individual aesthetics.

Video games, in the mid to high-end tiers of development where resources allow the developer to chase “realism”, feel like they’re stuck with similar ambitions to the realism that so many artists back in the 1850s embraced. And they’re becoming very good at it: look at how incredibly realistic Aloy looks and moves in Horizon, or how superbly the cities of Watch Dogs 2 or GTA are rendered. The battlefields in Battlefield or Call of Duty make no effort to hide the destruction and horrors of war (indeed, they revel in it), and FIFA games are at the point where you only need to squint a little bit to be convinced that you’re watching a real soccer broadcast. The problem the developers of these games face is that their work is dated from the moment it enters production.

Horizon is, arguably, the most beautiful game out there at the moment, thanks to its detailed, realistic environments and the quality of the Aloy character model. Leaving aside the robot dinosaurs for a moment, if you were to take screenshots of the world, you’d be left with the impression that the goal of the developer was complete realism.

But Horizon won’t be a beautiful game forever, because the power of the game’s art is contingent on those art assets being more realistic and detailed than anything else out there at the moment. At some stage – and it might be two, even three generations from now – we’ll look back at Horizon and think that its character models and environments are laughably simple. Aloy will look stiff and lifeless when compared to the heroes of those generational leap games. Horizon’s impact as a work of art will be compromised greatly as a result, because what drew people to it in the first instance is something no longer perceived by the viewer’s eye in the game.

There’s plenty of precedence to prove this. Back on the PlayStation 1, Final Fantasy VII, VIII and IX were considered to be masterpieces of epic scope. We can no longer talk about those games in those terms without adding “for their time” as a disclaimer. I distinctly remember Resident Evil 2 being lauded for its realistic environments and character models. Perhaps the most extreme example of all: remember the incredible controversies over Tomb Raider? To this day I recall reading a giant newspaper article about how Tomb Raider was going to usher in a new era of exploitation, with digital celebrities that can be made to strip down without their agents demanding millions of dollars in fees (I’m paraphrasing, because it was a long time ago I read this article, but that was its general thrust). Of course, we look back at Tomb Raider now and laugh ourselves silly that that mess of sharp, triangular polygons was ever considered “sexy.”

By contrast, abstract art in video games has proven, time and time again, to be timeless. At the most extreme end, you’ve got the early pixel work that went into Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Mario. These designs are cultural icons today, a sure-fire sign of their enduring artistry. There are less extreme examples: the sprite work of the original Super Nintendo Final Fantasy games was so beautiful that when Square Enix changed the art for recent mobile and PC ports, fans got very upset indeed. If those original sprites had lacked artistry, there would have been no controversy.

Those early 3D games that didn’t participate in the attempts to create realism have endured, too. Mario 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time never tried to be “realistic”. Instead, they made use of the limited number of polygons available in those early 3D engines to build environments, to create characters and spaces that were abstract, colourful, vibrant, and exciting. To this day these games look “simple”, but if an indie developer were to make a game that utilised similar aesthetics, no one would bat an eyelid at the art direction.

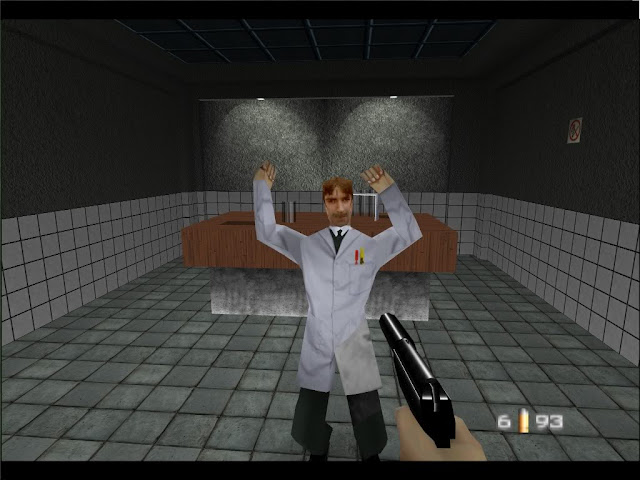

Meanwhile, if you made a game that looked like the – once – considered-to-be-realistic Goldeneye, (unless you were specifically targeting nostalgia for something now considered “ugly”), you’d be laughed out of game development.

When consoles of the power of the PlayStation 2 rolled around, cel shading became a common development tool, and again, it helped developers use this technology to build games that have, visually, remained attractive. Medal of Honor: Frontline or Resident Evil 4 remain good games, but look positively primitive compared to their contemporaries and now lack the “wow” impact those graphics had, as we are now “wowed” by the far more detailed hyper-real games by their respective developers, such as Resident Evil 7 or Battlefield. Meanwhile, XIII or Killer 7, for whatever faults they might have as games, continue to look as aesthetically vibrant as anything available in HD, as the emphasis is on art direction, not detail.

Fast forward to today. While Horizon will lose its shine as a great-looking game as other titles come along that have better engines and more realistic “graphics”, there’s a lot of stuff happening in the indie space that will never age. Visually striking games, like Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please, or minimalist masterpieces, like Mini Metro, will continue to have the same visual appeal decades down the track, just as people still flock to galleries to see Picasso’s unique, incredibly abstract understanding of art. While people stop playing a FIFA game when the next, better-looking FIFA engine lands, games like Danganronpa can never actually be replaced, because the visual impact is determined by the mind of the artist, not the engine and tools he/she had access to.

None of this is to say that there aren’t times the pursuit of “realism” is important. The Chinese Room absolutely had to target a photo-real aesthetic in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, because that painting-perfect recreation of the English countryside was the point of the game. It wasn’t thrown in there for some superficial reason, to look good in screenshots and sell more copies to people. The game’s art was part of its narrative, and as such it, too, will have everlasting value as a thematic masterpiece.

On a very different note: of course Dead or Alive Xtreme 3 had to chase “realism.” We’re talking about a “pinup game” in which the human-like models of the girls are the point of the game. Koei Tecmo could not abstract the art and expect it to appeal to people, even though it means the game will never have longevity as a work of art. However, the Hatsune Miku games, heavily abstracted as they are, will remain relevant into perpetuity.

If a developer is comfortable with their work having a limited shelf life – as the developers of the Dead or Alive games surely are – then that’s one thing. But it’s important that we realise that “realism” is a dead-end to longevity in this industry. The true works of art and the masterpieces that will be studied a century from now are the ones that put unique art direction and abstract visuals ahead of the hyper-real, and it’s important that, as we look at and play these games, we understand that realism is not necessarily the best path to take in terms of using a game’s art to enhance the narrative and context of a game.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld