I love a good spooky story; it doesn’t have to have jump scares, it just has to be deeply, deeply unsettling. That’s the kind of story told in Varney Lake, the second in a trilogy of Pixel Pulp games. I reviewed the first game, Mothmen 1966, about a year ago. It’s actually the Mothman connection that drew me to the series to begin with (though I called it a cryptid back then, and I’m no longer sure that’s the tea), and I enjoyed the new take on the Mothman mythos. Varney Lake again takes something familiar – vampires – and weaves them into a new, pulpy tale.

The Pixel Pulp series contains stories inspired by mid-20th century pulp fiction stories, with 1980s-style computer graphics. “Pulp” isn’t so much a genre of writing as a medium, as pulp magazines were called such due to the cheap wood pulp paper used to print the product. While stories of many genres were printed in these magazines, they’re perhaps best known for exploitative, sensational subject matter. The term “pulp fiction” emerged from these stories, and references generic, low-quality literature, things like detective stories and erotica.

So what makes Pixel Pulps pulpy? Thematically, it fits (they’re a sort of detective story, one could easily argue). But there’s also a productivity aspect to it: the production cycles are short, and the team works quickly and steadily. That being said, they’re like contemporary pulp fiction rather than classic pulp fiction: the idea of pulp is there, but the content is definitely geared towards today’s audience. The games can be consumed quickly, with minimal effort (it’s mostly a visual novel, with some puzzle aspects).

The main thing that ties Varney Lake to Mothmen 1966 is Lou, a detective-turned-writer who has fallen upon hard times in the early 1980s. He’s interested in writing a book about the adventures of three children in the 1950s, and interviews two of them. As a result, the game is half set in 1954 and half set in 1981.

In 1954, three adolescents are spending the summer together at Varney Lake, as they always do. Doug and Jimmy are 12 and 13, while Christine (Doug’s cousin) is a couple years older. They have formed “The Only Child Club,” as they are are kind of lonely only children. Jimmy has a huge crush on Christine, and it’s obvious, but he’s too nervous to act upon it. For a couple of years, the trio have been saving up to purchase an old drive-in movie theatre; their goal is to do so by the age of 18. The weird thing about the old drive-in is that people have reported seeing weird lights at night there.

So the summer is filled with crazy plans, game-playing (Doug loves to invent them), and even running from bullies. It’s that last thing that brings them to meet a vampire, and after doing him a favour he becomes indebted to them. This changes the summer and the future as a whole, as they begin chilling with Liszt the vampire and their dynamic shifts. One of them becomes close to the vampire, while the other two remain wary of his intentions. At the end of summer, one of the three goes missing and is never found. Unlike with Mothmen 1966, I’m not upset that a vampire has been made the villain of Varney Lake. It fits right in with what legends describe vampires to be (whereas Mothman is more like an observer than a villain, but I’m a purist).

Since Doug likes to make up games, there are several minigames to play. The first is something he’s invented called Solitaire Ten, which involves adding and subtracting card values to reach the number ten. There’s also a matchstick game. Unrelated to Doug is a fishing mini-game that I honestly couldn’t quite figure out on my own; this isn’t abnormal for me, unfortunately, as if a tutorial isn’t super detailed I lose track of what I’m supposed to do. Luckily, you can end mini-games without completing them. While I didn’t get stuck, I do feel like I missed out on something.

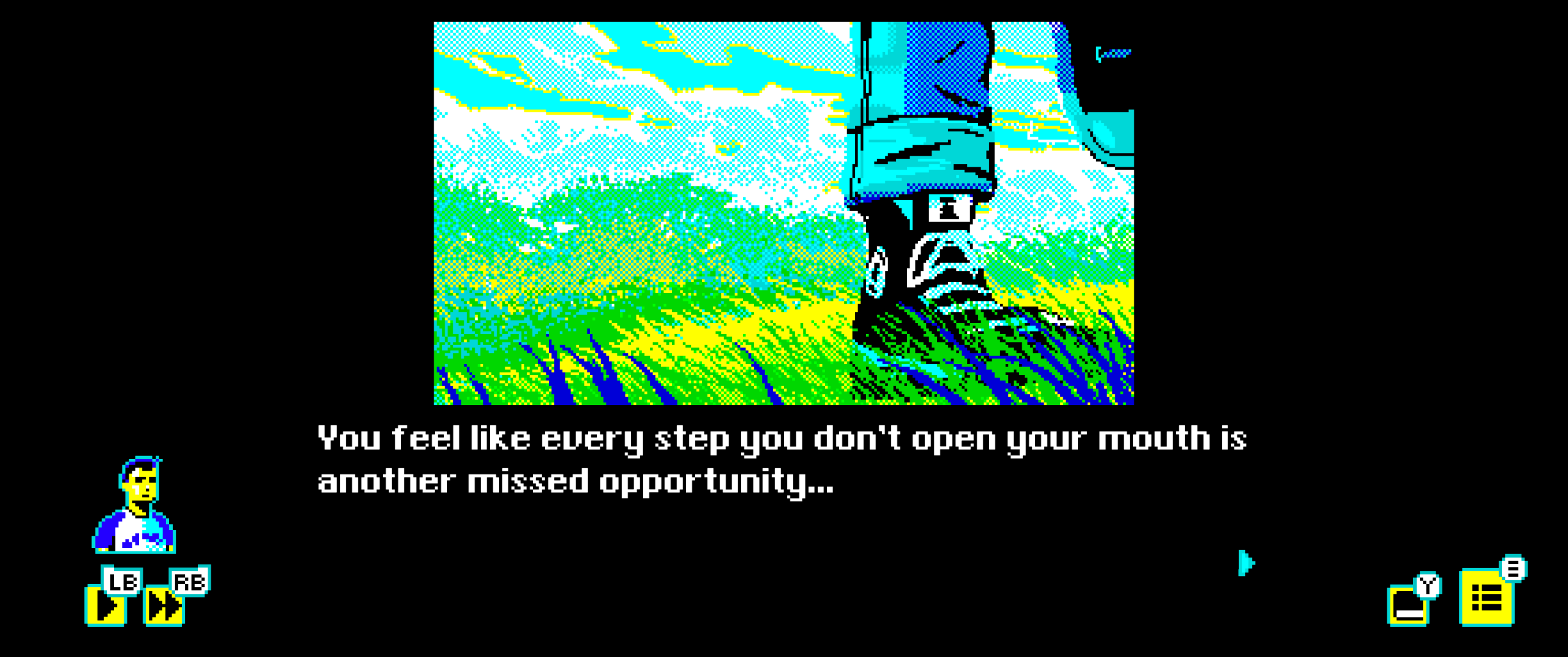

At its heart, I’d say Varney Lake – and by extension the other Pixel Pulp games – is a visual novel with some choice-making mixed in. It’s mostly reading and clicking, but every now and then you’ll get to decide what you want the players to do next. This works for straight-up choices (where to go), for environmental puzzles (like how to block light from unreadable windows), and for mini-games. It’s most interesting when used for the mini-games. I noted when playing Mothmen 1966 that playing cards with a visual novel selection format can be tedious, but by now I’ve gotten used to it (though I’ll always scroll in a single direction so I don’t get mixed up).

The story is definitely the shining star here, and I really appreciate how it seems to suit the retro-styled, limited colour graphics. I can tell a lot of care went into the visuals in the Pixel Pulp series. Each has its own colour palette, and up against each other the screenshots are noticeably different while also tying together. When it comes to sound, it feels classic and well-matched with the visual era being pulled from.

There are a couple technical issues I encountered. One, you can’t change the screen resolution or aspect ratio from the in-game settings. It’s not a huge deal, since it did auto-detect an ultra-wide monitor correctly, but it’s something I felt was missing a little bit. Two, either I’m missing something obvious, or the only way to exit the game is to force quit. Neither of these things break the game or make me not want to return to it, it’s just worth noting.

Varney Lake was, at its heart, exactly what I expected it to be: a mystery story, a horror story, and a coming-of-age story all rolled into one neat package. There’s even some surprises in there. Playing Mothmen 1966 first was definitely useful for referencing characters, but it’s not absolutely necessary to play it first. The developer did a wonderful job at creating an immersive experience while confined to the visual standard it set for itself. I’m eagerly awaiting the final title in the series: Bahnsen Knights is about a cult. I’m also awaiting further news on the recently-announced Pixel Pulp physical edition for Nintendo Switch, which I will definitely be adding to my collection.