Most tourists visiting Tokyo probably don’t go anywhere near Yumenoshima Park, located in Koto City, though they probably inadvertently glance in its direction once or twice because it’s basically just around the bay from Tokyo Disneyland, albeit in a significantly more industrial area.

Well, actually, I wouldn’t know, I’ve no plans to do Tokyo Disneyland any time soon, for all I know it’s built on toxic swamplands. But what I do know is that the walk to Yumenoshima Park involves strolling down the sides of some busy highways. Nowhere in Tokyo is truly “remote”, but this is definitely off the beaten path, especially for non-Japanese visitors, and I’m all the while hoping that Google Maps hasn’t sent me on a wild goose chase.

Or in this case, a wild kaiju chase.

I’m a big fan of Toho’s Gojira movies (or Godzilla, I’m flexible with the pronunciation as Toho itself is), and like many I’d presumed for years that the genesis story of the world’s best Kaiju (Gamera and Kong exist far in his shadow, and you know I’m right on that in every way) was simply based around Japanese reactions to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the closing days of World War II.

However, it’s nowhere near as simple as that, because the reason why I’m visiting a somewhat remote park in a non-tourist part of Tokyo has a far more central role to play. To understand why, I’ve got to give a quick history lesson.

Japanese anti-nuclear positions don’t really start with Hiroshima and Nagasaki

When the US military made the decision to use nuclear weaponry on Japan, it did so fundamentally to send a message. This was not a subtle message, and it affected the lives of millions… but it was a rather pointed message designed very specifically to reach Japanese high command in an effort to shorten the war considerably. That’s who the Americans wanted to reach.

Once the peace settlements were signed, however, the US found itself in effective control of Japan, and it wasn’t anywhere near as keen on messages getting out about its nuclear weaponry use.

So paradoxically while US publications could write about atomic weaponry and its effects in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, doing so in Japan under US rule could land you in a lot of trouble. It wasn’t that the populace was completely ignorant, but there was certainly considerably less awareness because of the blanket media bans in place under US occupation.

Jump forward just a few years to 1954. The US is no longer in control of Japan, but it’s still busy working on nuclear weaponry, especially in the South Pacific, where it pursues a policy of testing on remote islands where (in theory) nobody but US nuclear scientists will be aware of what’s going on. It did periodically issue warnings of tests going on so that shipping and fishing boats would not stray too close, including notifications to the Japanese Maritime Safety Agencies.

Japanese fishing boats weren’t always notified entirely accurately about the risks involved here, and on the morning of March 1, 1954 – at 6:45am precisely if you happen to have a time machine – the US set off a hydrogen bomb with what was meant to be a 6 megaton explosion. Only, well… it wasn’t quite measured properly.

It instead had a yield of 15 megatons of TNT, or (by most estimates) something like a thousand times the power of the “Little Boy” bomb that had levelled Hiroshima nine years earlier.

A big bang indeed, and something of an environmental black eye… but also a big problem for the unwitting 23 man crew of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, (AKA “The Lucky Dragon 5”) a tuna fishing boat that figured it was well outside any exclusion zone that morning, given it was around 130km away from

Most of the crew were asleep, and were woken by the sky lighting up far brighter than the sun. Minutes later their boat was rocked by the force of the explosion, but the worst was yet to come, in the form of radioactive fallout, specifically from absolutely pulverised and highly radioactive coral ash.

The crew worked through and around the ash, with at least one crew member at least trying to taste it, absolutely unaware of the quite lethal risk it posed to them. As night fell, it became considerably clearer to them that it was a huge problem, with multiple crew members displaying a multitude of sickness problems. They returned to port as rapidly as they could, where they were placed into quarantine and decontaminated as best could be managed by 1954 standards. It didn’t make much difference to many of them; within six months the first crew member died as a consequence of his exposure.

This, then, was a nuclear weapon story that could not simply be hushed up as a wartime matter, and it led to fierce anti-nuclear sentiment in Japan. Within a year, more than a third of Japan’s entire population had signed a petition looking to ban nuclear weaponry.

All of this sounds fascinating, but what does this have to do with Tokyo port parks and Godzilla?

As to the big Kaiju lad, well, his first movie (of many – there’s a new Japanese Gojira movie due out later this year, and I’m fervently hoping it gets some kind of Australian release; trailer below) was released in late 1954, absolutely and directly inspired by the anti-nuclear sentiment that flared up around the Daigo Fukuryu Maru incident. A little exploitative? Maybe, but it genuinely tapped into the public sentiment and fear at the time, and it’s why that first movie has such a particularly chilling tone that later films abandoned in favour of spectacle and often outright comedy.

Godzilla (1954) trailer

There’s a reason why there’s a burning boat at the start of that movie – and a reason why it’s named rather similarly to the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, too. Without that public consciousness (and, to be accurate, Toho’s rapid need for a film in a schedule that had seen an Indonesian co-production collapse earlier in the year) we don’t get Godzilla, or likely the many other Kaiju competitors to his throne.

Godzilla Minus One trailer

Also we don’t get Godzilla video games or pinball games, including the recent superlative Stern Godzilla. If you’ve not played that game and you like pinball, track it down. It’s amazing.

So that’s Godzilla sorted, but why then am I in Yumenoshima Park when I could be in Akihabara, or Shinjuku, or Shibuya or any other much more tourist-centric location?

It’s because in the middle of Yumenoshima Park sits a stark triangular building, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall.

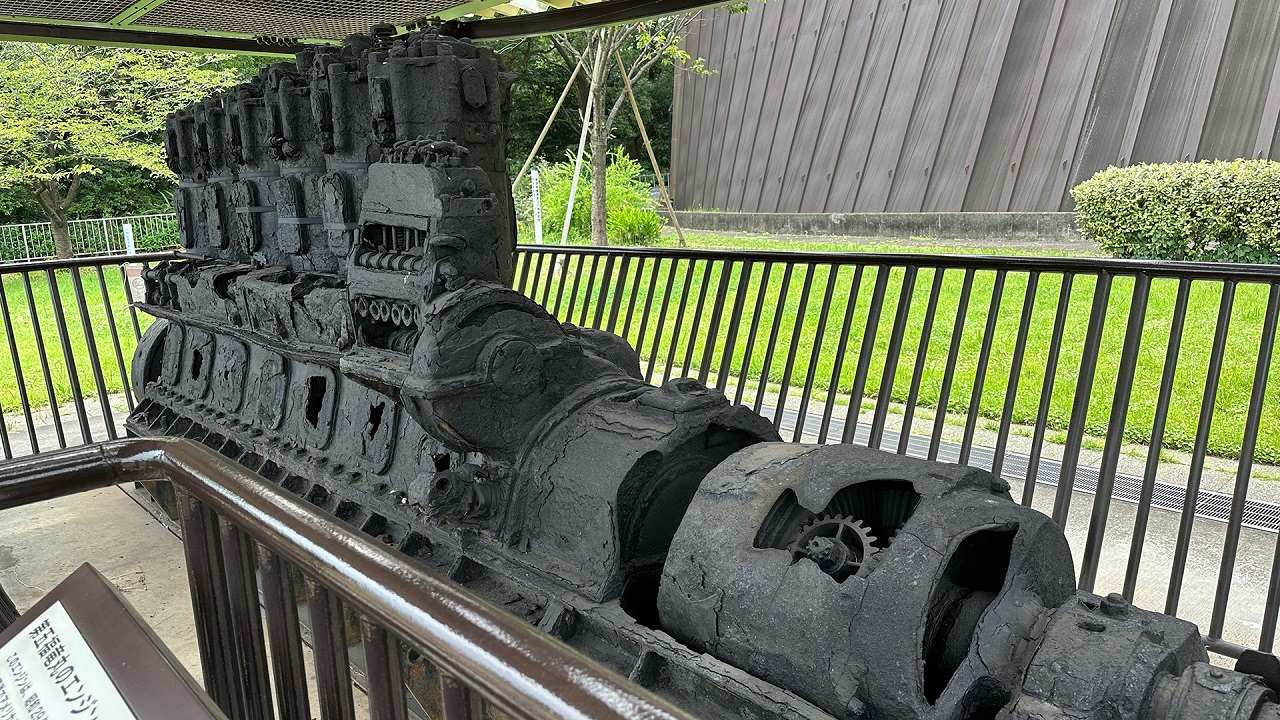

This isn’t just a dusty museum with a couple of newspaper clippings and a tacky gift shop. Because, rather astonishingly, this is an museum that houses the actual Daigo Fukuryu Maru. The actual boat, that is. Astonishingly once it had been cleaned and decontaminated it continued to ply its trade, albeit under a new name and as a training vessel. It was very nearly just left to rot once that use had been exhausted – and its engine was placed into an entirely different boat – but further outcry led to it being hauled to land and placed in the exhibition hall.

Which is kind of amazing, but then to add to that, this isn’t a boat museum to speak of. It’s a monument to the victims of nuclear power worldwide, or hibakusha. The hall documents the fate of those unlucky 23 fishermen, but also statements of those affected by nuclear weapons tests around the world, including Indigenous Australians; of note here while I’m unsure as to the specific customs of that particular mob, it’s almost certain that it contains images and comments from those affected by the Maralinga nuclear tests who have now passed away, if that’s important to you.

The boat itself is immense and genuinely overpowering. It’s quite safe now, of course, but walking around underneath and beside it, I can’t help be hit by the weight of history that it represents. Visiting the Daigo Fukuryu Maru is extraordinary; a mix of something that’s brought me one of my absolute true favourite parts of Japanese pop culture, but also a genuinely emotionally confronting and vitally important exhibition.

And if you can’t make it to Tokyo any time soon, luckily I did – and I captured more than a little video while I was there: