For years now Steins;Gate has been renowned for being one of the finest visual novels ever produced. First released way back on the Xbox 360 in 2009, it has been ported to PC, PSP, iPad, Androd and, now, the PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Vita. There has even been an anime based on it.

It’s rare for any game to enjoy this kind of longevity, let alone one from a genre as niche as the visual novel, so there’s a good reason for that, right? And there has got to be a good reason that PQube would think to release yet another new edition of the game, so many years after it first started making waves, right?

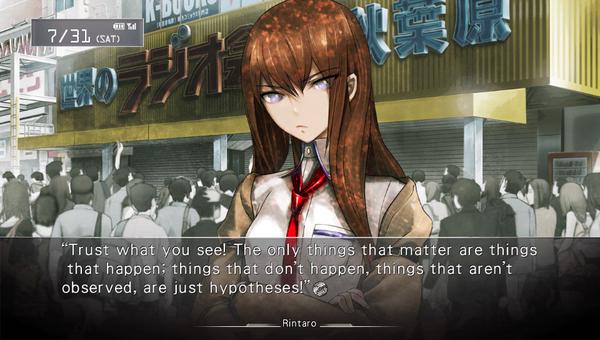

And so Okabe believes he’s of an intelligence to engage in debate over time travel and other such high-end science topics with actual genius scientists. He can’t, of course, and in the early stages of the game we have a great time laughing at this utter loser and his delusions of grandeur. It’s especially amusing when, in one scene, the aforementioned genius calls him out for talking on a phone as though he’s passing on sensitive information to his allies. But the phone isn’t turned on. The allies don’t exist.

But then something happens. Somehow Okabe and his friends discover that they have developed a time machine, entirely by accident. And then they discover that a science organisation called SERN (CERN renamed to avoid a lawsuit) has also discovered time travel, and is experimenting with it with disastrous results (that it is actively covering up). In other words, Okabe’s delusions start coming real, and then everything starts becoming very serious indeed.

The narrative reminds me in an odd way of that old Mel Gibson film, Conspiracy Theory, in that a crackpot somehow lucks into something real, and the narrative then tries to explore the fallout of that. It provides for a fun mystery structure that will keep you on your toes throughout, constantly second guessing whether what’s going on is real or not, and because Okabe is so unhinged and has difficulty telling reality from fantasy, there’s a constant sense throughout that you’re seeing the eyes from the eyes of a very unreliable narrator.

The unreliable narrator is a concept coined by important literary critic, Wayne C. Booth, in his book The Rhetoric of Fiction, and has become a major, recurring theme across many films, books and games. It’s a concept that is so compelling to both writers and audiences as it provides a direct challenge to the relationship between the audience and the author – we’re provided with a point of view, but we can’t be certain of it (because the narrator can’t be trusted), and so we start to question what that means to our broader understanding of the narrative. To break it down further, Steins;Gate’s narrator, Okabe, could be classified as a “madman”-type unreliable narrator, where his disassociation with reality makes it difficult to fully appreciate the emotional connections between characters or, indeed, the kinds of personalities they would exhibit were they freed of the lens of Okabe’s delusions. Steins;Gate isn’t written quite as well as some of the classics within this genre, perhaps (given we’re talking about authors like Kafka and characters like Patrick Bateman there’s no shame in that statement), but nevertheless, the way the story plays out is intensely interesting and evokes some vivid imagery along the way.

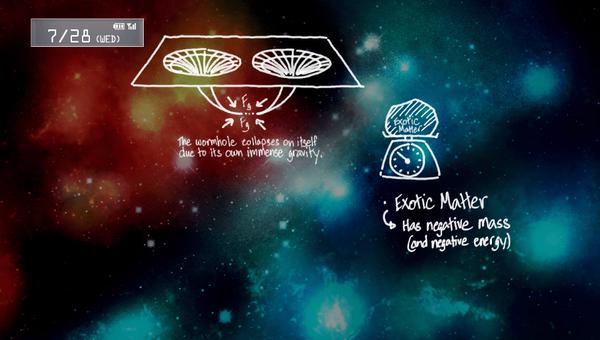

Steins;Gate is assisted in its ability to keep players in a permanent state of uncertainty by its eloquent use of science and technology, both real and the mythologies that are tied to it. It provides a remarkably clean summary of the underlying theories that would, in theory, enable time travel, and then uses those in the context of a world in which John Titor (a early Internet celebrity that set the place on fire by claiming he was from the future) is a legitimate time traveller. This was a game that I played with Wikipedia open nearby so I could keep checking the terms it used against how they apply in real life, and it was fascinating to see how they were woven together. I even learned some new stuff, and any game that inspires me to learn is instantly in my good books.

So in terms of its literary merit, Steins;Gate ranks quite high, and I do think people studying the construction of narrative will find value in adding this to their “reading” list. It’s still the equivalent of a page turner, with a dry and black sense of humour at times, and the characters are strong and when the drama does ratchet up, you will feel sympathy for them where you’re meant to, but equally importantly, it’s a narrative of intelligence and offers room to study on a deeper level if you’re so inclined. It’s rare for games to do that, still, and those that do should be applauded for it.

The presentation is gorgeous too, and Steins;Gate is a textbook example for how a distinctive art style can enhance and help develop a narrative. We rarely see Okabe himself, but rather we see the world through his eyes, and the dreamlike quality of the aesthetics subtly reinforce how unreliable his perception of reality is. The odd moment where we do see Okabe from a third person perspective tend to be the most interesting parts of the entire game. Early on, for example, we’re treated to a scene where Okabe goes on a long diatribe talking directly to us through the screen. We discover later that he’s talking to a character in a video game that’s he’s playing, but while it’s going on it’s an impressive fourth wall-breaking scene that sets us up with a direct relationship with the character and his less pleasant personality traits.

The only interactivity on offer through the game is the ability to respond to some emails that come through to Okabe’s phone on a periodic basis. These emails will offer a handful of different responses, and your decisions there will generate one of a number of endings at the end of the game. Each of these endings are worth experiencing to understand the full gamut of themes that Steins;Gate touches on – and I really have only highlighted a couple of them above.

Related reading: For an alternative visual novel experience, check out Hakuoki.

It’s quite a long visual novel, but Steins;Gate is, like a good book, hard to put down. It’s subtle, but it plays into all the strengths of the interactive game medium and uses them to enhance its narrative in such a way that the story it tells wouldn’t be possible in a book. I strongly suspect that, a hundred years or so down the track, Steins;Gate will be remembered as a truly classic narrative, for it is both entertaining and intelligent. Your grandkids may well be playing this one for their high school class assignments, and that’s a pretty neat thought.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld