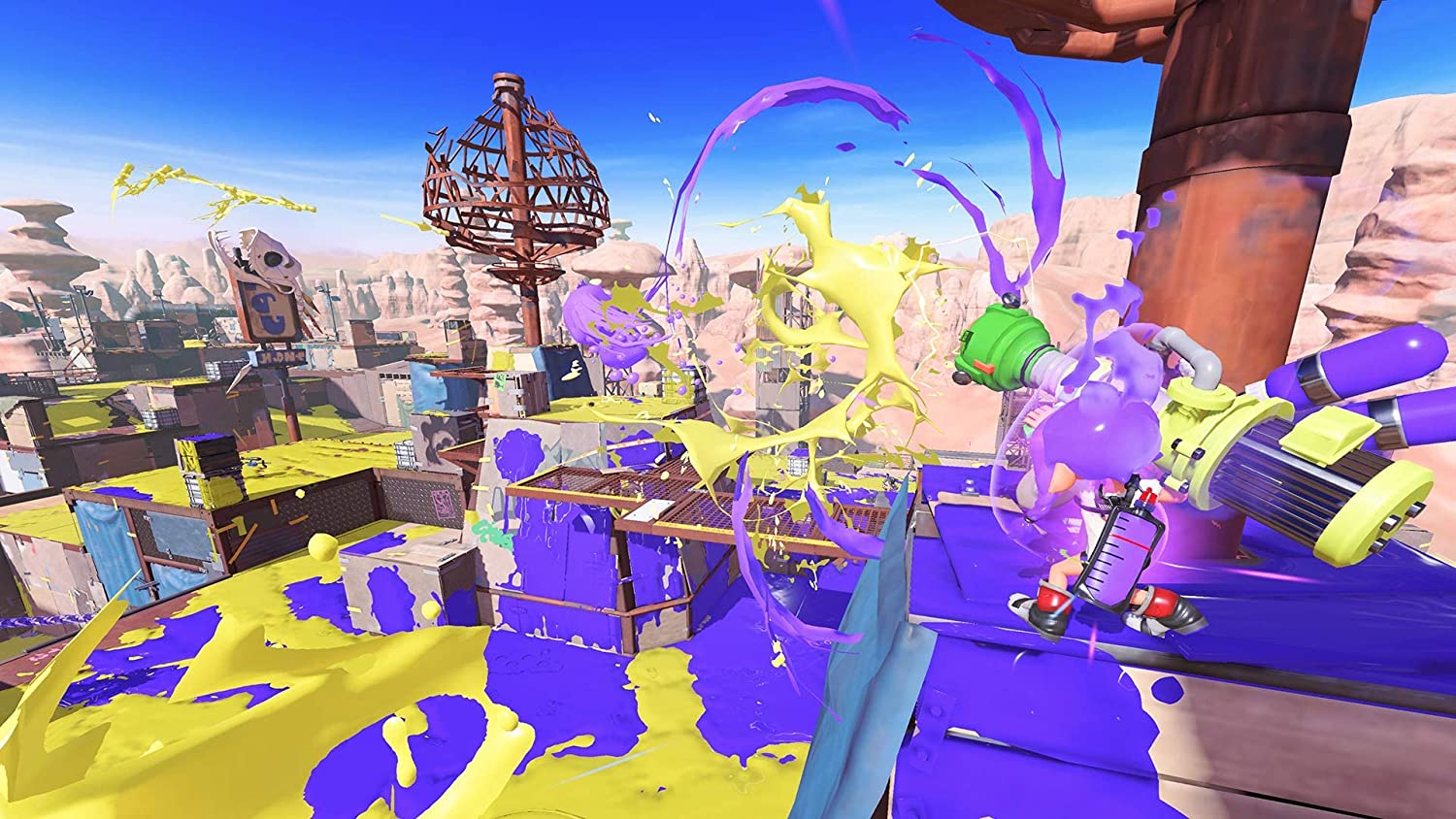

One thing I can say in Splatoon 3’s favour right from the outset is that I’m finally not being struck down with migraines while playing the game. With both Splatoon 2 and the original, the extremely busy, bold, messy and overwhelmingly bright colours seemed to trigger something in my brain that very few other games have ever done, and if I played for more than a few short minutes at a time I was almost certainly going to be slammed with a splitting headache. Once, with the original Splatoon, it lasted for days. I can’t pinpoint exactly what it is with Splatoon 3 that means it’s easier on my brain, but – touch wood! – I’ve been able to enjoy this one headache-free. And I’ve been playing for some pretty lengthy sessions, too. This is good fun.

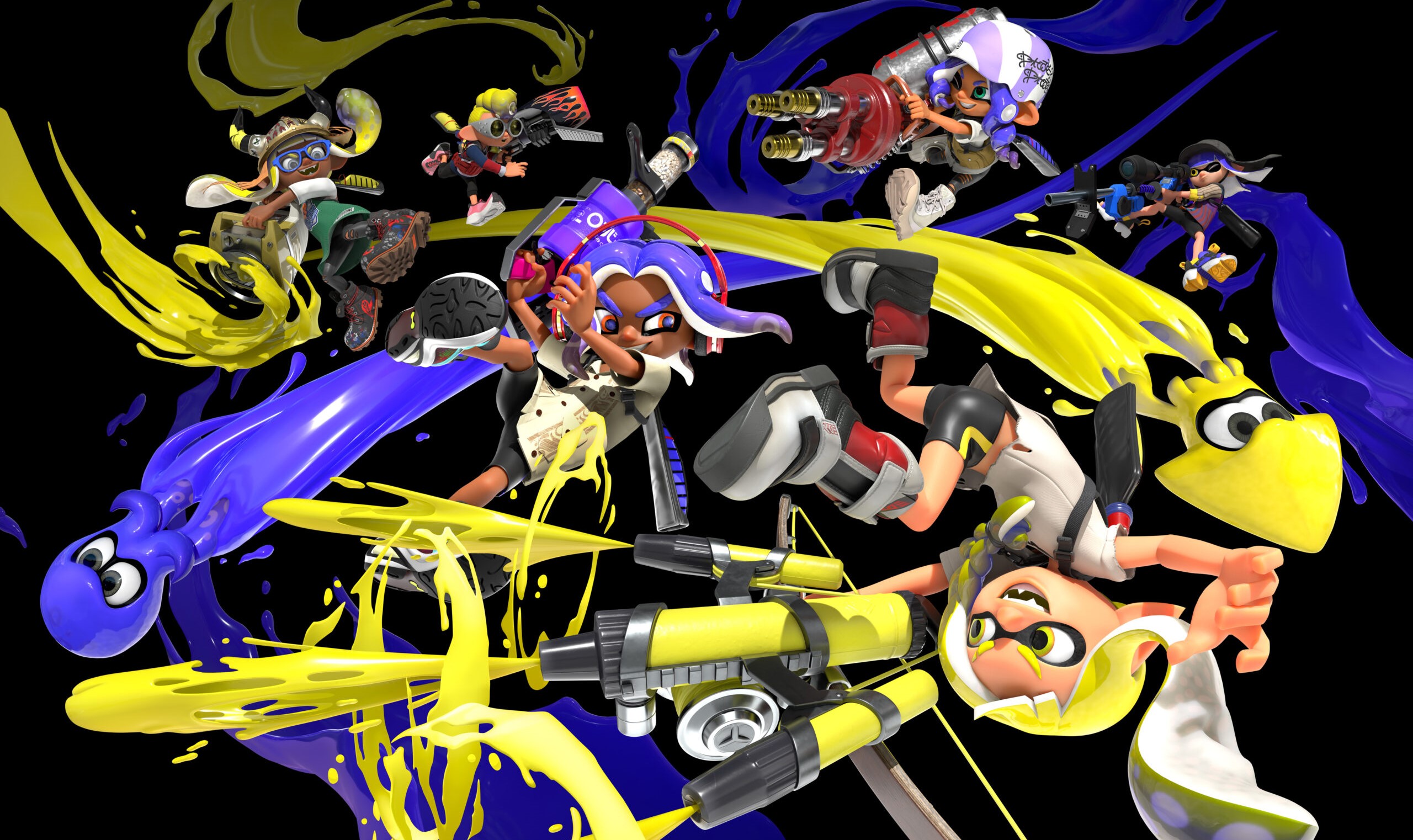

With that being said I don’t think I’m ever going to love the aesthetics of Splatoon. The blend of childpunk and hyper-colourful street graffiti-tude is popular, and the success of the series is a testament to that. I’m not here suggesting that it needs to be changed to suit me. It’s just that it’s not my kind of thing. Not that it matters, though, because I do love playing Splatoon despite the aesthetics, and for the reasons above, I’ve finally been able to play it for extended periods, and enjoy it for all the good that it does do.

One of the great things about Splatoon as a multiplayer experience is that you can enjoy it without having to deal with the hardcore fanbase. Assuming that you’re not going to go out there and try and be a world champion player, it’s perfectly possible to play, and feel like you’re participating, without having to communicate. Levels are nice and small, and people generally know how to get about the job without being a drag on the team. You’ll often see opportunities to help allies out, they’ll come to your rescue from time to time, so you feel like you’re part of a team. Then, as long as you stick to that basic level of camaraderie, you’ll always be in with a fair chance of victory and blowouts are rare indeed. There are some really basic commands that you can throw to your teammates if you do want to follow through with a particular strategy, but thanks to the brief nature of matches, even if your teammates do ignore your Napoleon-like tactical genius (which, in fairness, is usually the case), even losses are not that disappointing.

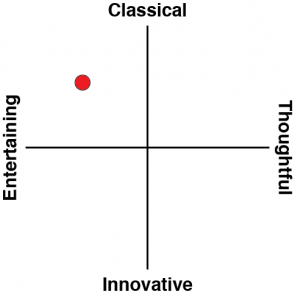

Splatoon is an excellent casual shooter option, in other words. Where other shooters, from Overwatch to Fortnite and on to Call of Duty, all but demand you approach them with the focus and commitment of serious work, Splatoon and its userbase won’t care if you log in once per week and have no chance of turning professional. The game’s just not tuned that way.

If you do want to take it seriously, however, there is a long and generally rewarding journey toward mastery in Splatoon. Not only are there more weapons in this third edition (though personally, I’ll never swap from my favoured dual pistols), but there are more special weapons than ever, too. Now, whether it’s using a zipline to drop deep behind enemy lines, or placing a shield in the right spot to protect a flank, there are a lot of very fast tactics to come to grips with. In fact, while Splatoon 3 is only an iterative improvement over its predecessor, there’s enough there for it to feel like the improvements are substantial. And yet, even for the newest of players, none of this will be overwhelming. You’ll need to be a little patient with it at the very start, but as Splatoon’s nuances start to make more sense, the majesty of the overall experience will quickly hit home.

With Splatoon 2, Nintendo worked hard to deliver a single-player mode that people would love to complement the multiplayer, and Splattoon 3 continues that effort. As a narrative, it didn’t do much for me (though, thanks to the aesthetics I was already inclined to be disinterested in that regard), but what is good is the difficulty curve (some of the levels are going to really test players), as well as the imaginative and creative nature of the levels. These are not simply a case of “move from A-Z, shooting everything in between.” Rather, every level has been an opportunity to throw something different at the players and make them look at it differently.

Another fun alternative way to play is Salmon Run, which is the cooperative horde mode spin on the Splatoon action. This mode comes across from Splatoon 2, and has been tweaked nicely. Now you can play it at any time (previously, in Nintendo’s infinite wisdom, you had to be online at specific times for that one), and while it’s only ever going to be seen as a break from the other game modes, it’s a welcome one thanks to the purely positive co-op spirit it encourages.

What is incredibly disappointing, however, is TableTurf, which is new, and can be best described as “card-based, turn-based Go”. The problem is not the minigame itself, though. The minigame is excellent. In TableTurf, the goal is to fill up a play field with ink using “cards” that have different ink splat layouts on them. Have more spaces filled in at the end than your opponent, and you’re the winner.

Like with Go itself, TableTurf is tactically interesting and an inherently challenging board game. It would have been great to play this competitively. Indeed, as a person that is much more drawn to turn-based strategy and card games, I could easily see myself focusing on that minigame, and it is of a high enough quality that it could draw a small, but competitive community around it. It could have been like mixed doubles is to tennis, with a small but dedicated audience getting really good at that particular niche that while the mainstream players focus on the singles or doubles competition. For now, however – and this is where the disappointment kicks in – TableTurf is currently single-player only. Yep, that’s right. Nintendo developed a competitive card minigame and then locked it to AI battles. In a multiplayer-orientated game. I do hear that Splatoon 3 will be updated to include multiplayer competition down the track, but who knows when (or if) that will eventuate in reality. For now, it’s the one disappointment in an otherwise compelling showcase of gameplay variety and depth.

It took Nintendo just three releases to turn Splatoon into one of its biggest and most valuable properties, and it’s easy to understand why. It’s not complex: Splatoon is something that almost everyone can enjoy. For those who want to be competitive, the blend of weapons, items, and abilities gives the game plenty of nuance, and there’s a true curve from beginner to excellence. For those that just want to jump in and have a blast, it’s a game that’s welcoming, has an excellent single-player mode to onboard you, and never feels like it’s punishing you if you spend less time playing it than others. At a time when online play is becoming increasingly hostile to anyone who isn’t willing to make the game their entire hobby, it’s nice to have a company like Nintendo remind us what it’s like to have simple, uncomplicated fun in online multiplayer.