I should love Dark Deity more than I do. The developers clearly have passion for what they’re doing, and the thing that they’re doing is copying one of my favourite games of all time. In its entirety, Dark Deity aims to clone the two Fire Emblem titles that were released on the GBA – you know, the ones with Lyn and Eirika – and clone them to an exacting degree. The game doesn’t have so much of a hint of originality about it. Unfortunately, while the developers clearly understand what made those first English Fire Emblems so beloved, they also failed to reach the same highs.

It’s all here in Dark Deity. There are the weapon triangles, with some heroes having an inherent advantage against others. Then there’s the relationship system, whereby certain characters that fight closely will eventually deepen their bonds, which boosts their effectiveness in combat after you watch a cut scene of them batting eyelashes at one another. There’s a similar levelling progression system, too, with the only real difference being that you have some limited control over what classes characters can specialise in as they hit high enough levels. It’s no exaggeration to say this: pixel-for-pixel, Dark Deity plays exactly like Lyn’s adventure, and that is not an inherently bad thing.

The narrative, meanwhile, pitches in the same ballpark too. It all starts out with a group of kids – yes, actual child soldiers – being rushed through a military readiness exam so that they can be dragged into a war of attrition that their mad king has thrown his under-resourced army into. Before they can join the frontlines, however, this group need to battle their way through some bandits (because every Fire Emblem starts with bandit battles), and midway through things take a distinctly fantastic and epic turn that goes well beyond the machinations of a power-mad king. If you’ve played a Fire Emblem game before then you know what to expect, and I suspect that just saying that will come across as a compliment to the developers, since that’s all they actually wanted to achieve in the first place.

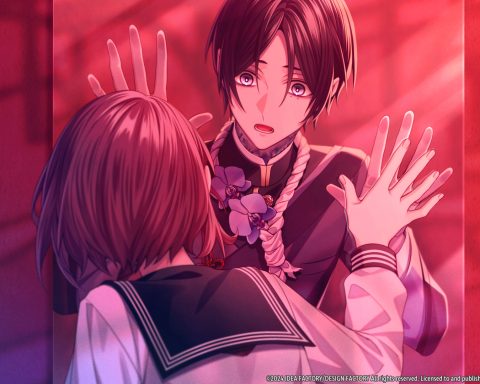

Finally, visually the game tries to behave like a Fire Emblem GBA title too. The character portraits are a best effort at recreating the gorgeous art behind Lyn and company, the battle maps feature the same top-down-and-cute-sprites quality, and when a battle is joined you do indeed get a little cut scene of the hero and their enemy duelling it out. Once again, through the visual design, the whole project very much comes across as the developer’s best effort to fool us all into thinking that we’re looking at a long-lost Fire Emblem title.

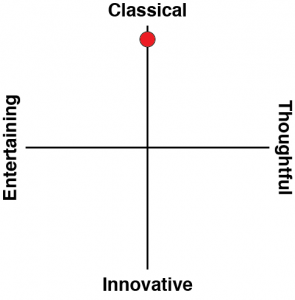

However, for this review, we need to now talk about pastiche. It’s an art term and it often carries negative connotations. People will typically use the word “pastiche” in a derogatory manner as a synonym for a “copy” of another work, and the derivative nature of the second work is, in the context of the way the word is used, meant to be considered as something inferior. Sometimes it does work out that way. In 1998, for example, Gus Van Sant remade Psycho, nearly shot-for-shot, and was so slavishly indebted to the Hitchcock masterpiece that his own project was considered soulless, and went as far as to receive Golden Raspberry nominations. That’s a very poor pastiche indeed.

But other pastiches can be excellent. The Lion King is a pastiche, taking Kimba the White Lion from Japan and recreating it for an American (and global) audience. Star Wars was a pastiche of Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, and Quentin Tarantino fills his films with pastiches (often from Asian cinema) as a near-standard aesthetic and stylistic motif within his body of work.

Pastiche can result in a work of art being a parody, or it might result in it taking on kitsch qualities. And there, too, it can be both a good thing for the work, or not. In almost all cases, the line separating the two is quite simple: the audience should be asking whether the pastiche uses the base material in such a way that it ends up having something of its own to contribute. A good pastiche might be subversive to the original work’s ideas. Perhaps it’s made in serious homage, but recontextualised for a different audience. Or perhaps it’s postmodernist and metatextual in tone. Over the last two weeks at DDNet we’ve been obsessed with Stranger of Paradise, as a “reimaging” of the original Final Fantasy 1, and that is a great example of a pastiche in just about every (positive) way that I’ve listed above. As a result, it stands out as an excellent work because it’s quite easy to see how it forges its own take on the work that “inspired” it.

Unfortunately, Dark Deity is the other kind of pastiche. Its greatest failing is that it does come across as an inferior clone to those games that inspired it. Being inferior to one of the greatest games ever made is nothing to be ashamed of in and of itself, but in every area Dark Deity just falls short. The maps aren’t quite as memorable or well designed. The characters aren’t quite as lovable (in fact, as I write this, I can only vaguely remember characters and names, aside from Cia, a most excellent rogue). The art is inspired by Fire Emblem, but aesthetically lacks that last 10 per cent. That brings us to the ultimate problem with a slavish pastiche: if Dark Deity stood for something else – anything else – then all of the above would have mattered less, because it still would have had its own identity.

However, without its own voice, Dark Deity is, simply, inferior in every way to the great. It’s still made well and familiar to genre fans, but I wasn’t looking forward to character interactions between levels in quite the same was as I did with Fire Emblem, because they went on for too long and I didn’t care about the characters enough. I let levels float on past me because, while I enjoyed in a basic way, I also wasn’t as engrossed in pouring over the maps to try and figure my pathway forward. Soon after I started playing, Dark Deity became a game I would play while watching TV, but never so deep in the night I almost forgot to sleep.

However, I do want to mention something else: this is the first game for the developer, and most great artists start out producing pastiches. For just one really good example: we all know Salvador Dali as the great artist of the surrealist movement. What fewer people realise is that he started out painting deeply forgettable and uninspired impressionist works, under the mentorship of impressionist, Ramon Pichot. Were Dali not to break with impressionism and find his own style, his body of work would have been remembered as a very distant pastiche to the style of Monet and Degas.

It’s hard to develop your own voice until you understand how other artists find theirs. While I ultimately find Dark Deity to be uninspired and certainly won’t be replaying it every year or so, as I do Fire Emblem, I also hope that this developer produces another tactics JRPG. I would buy that in a heartbeat, because I am quite certain that with a bit more experience as a team of artists, not only will this developer find its own voice, but it will start to build on everything that made those GBA Fire Emblem titles great. That – the promise of some kind of “Fire Emblem Plus” – is some exciting promise indeed.

Yes, you can see the relationship system play out much as it does in a Fire Emblem game, with the little heart icons during battle and eventually with cut-scenes. But the game itself will tell you that there is no tactical advantage to this system. It doesn’t lead to any in-battle perks. My own suspicion is that they hoped at some point to implement that, but ran out of time, money, whatever.

Hah! Shows how little attention I was paying at points (there were some bits where I was just mashing “A” and watching TV instead, I must admit. I could have sworn I was getting small boosts when close allies were working close together, but I guess that was just a psychological trick I was playing on myself. Thanks for clarifying!